In 2021, as the mayor of Moab, a small city in Utah, Emily Niehaus never intended to drop everything and start a school. But that was exactly what she did.

Niehaus did have a background in education, but she’d been a mom for more than a decade, and in that role, she saw a problem.

“My son needed an alternative, and the alternative to starting [a new school] was leaving my community,” Niehaus explained. The only suitable school she found for Oscar was in Los Angeles — and moving wasn’t an option. “That was a nonnegotiable for me and my husband. So we just had to figure it out.”

Niehaus’ son, Oscar, was in sixth grade at the local charter school. Oscar has autism, ADHD, and is gifted — meaning he is “2e” or “twice exceptional,” having both a disability and talents that exceed his age group academically. Moab, a city of only 5,000, is limited to what the public school district could provide.

“We’re ‘both rural,’ which means small in size and remote — two hours away from the nearest Walmart,” Niehaus said. “Our school district offers one middle school and one high school, and that’s it. For kids like my son who are neurodiverse, there wasn’t enough opportunity for him at the public school.”

Niehaus knew she was best poised to deal with the issue, so she decided not to run for mayor again and dove headfirst into starting Heron School as a place where neurodivergent students can receive individualized, project-based learning that helps them thrive.

“I have amazing grit and willpower, and I’m scrappy,” she said. “I figured if nothing else, [Oscar] and a handful of friends could learn alongside each other.”

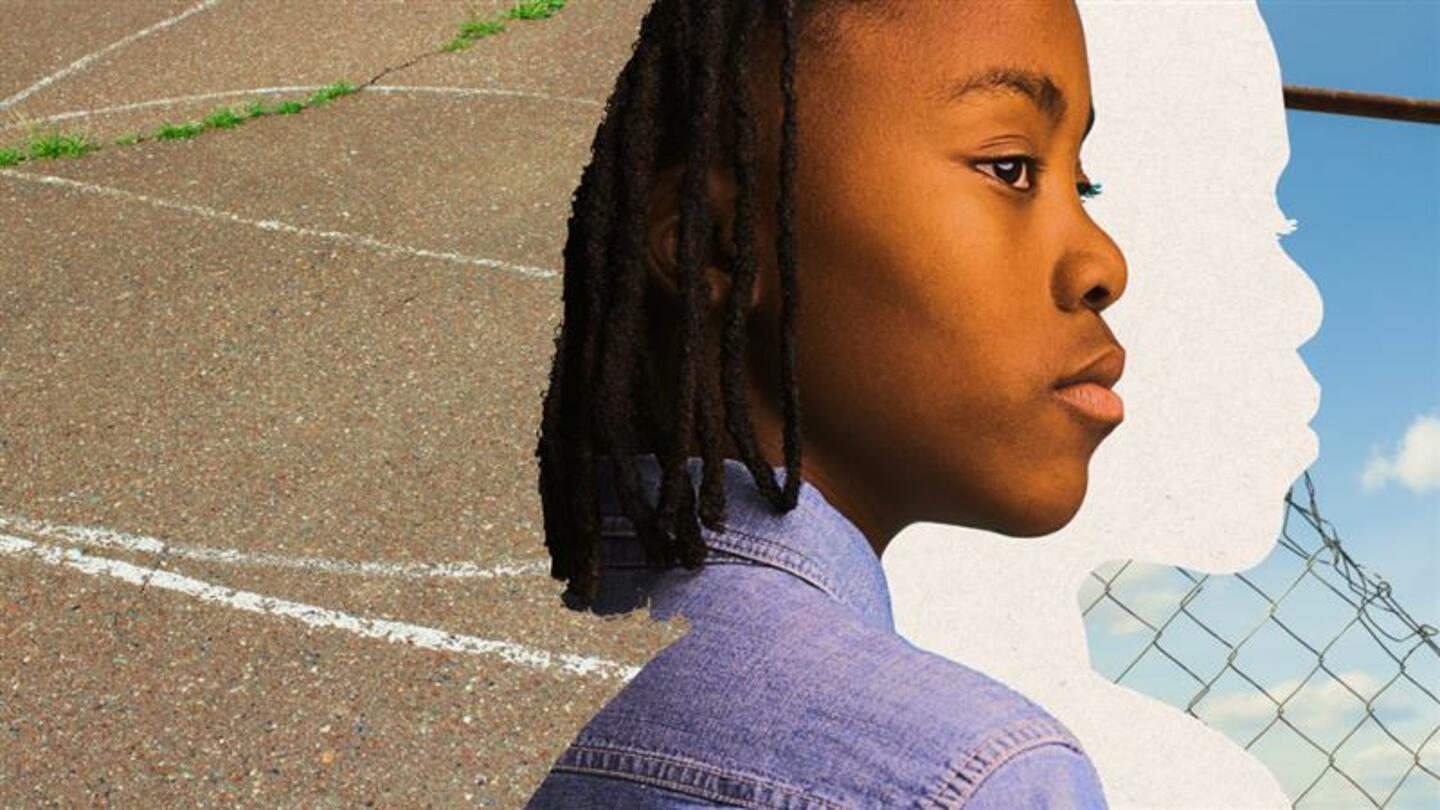

![At the Heron School, neurodivergent students have a space where they can learn at their own pace, in a style that meets their needs and strengths.]](/sites/default/files/2024-11/heron%20school%20photo%201_0.jpg)

In doing so, Niehaus demonstrates an important reality of an increasingly diversified education landscape: The available school ecosystem doesn’t work for everyone, so parents and entrepreneurs are designing and creating options that best serve the individual needs of their community. Tapping into these professionals’ unique backgrounds and strengths leads to creative, personalized, and diverse education models specifically designed for the needs of their learners.

The obstacles, lessons, and priorities Niehaus has picked up along the way can help others looking to branch out into alternative education, whether that means founding an entire school, trying to build on offerings within the public school system, or creating other alternatives.

Her biggest lesson? Don’t be afraid to experiment and take chances. “What’s the worst that could happen?” she pointed out. “You fail?”

According to her, that’s just a necessary step toward growth.

Becoming an ‘edupreneur,’ no teaching degree necessary

Niehaus speaks fondly of Moab’s beauty: the orange sandstone, the high desert, and the vexing task of limiting outdoor hobbies to just three, especially when rock climbing season is in swing.

However, the same wild beauty that makes her community so valuable is also a big obstacle, illustrating a catch-22 for education entrepreneurs. The places that lack alternative options are more likely to lack the resources for building new options. Niehaus’ biggest obstacle when founding Heron, she said, was finding teachers available to staff an alternative school.

“I’m just always frustrated by the lack of resources in my rural and remote community,” she said. “I choose to live here because it’s beautiful, and I’m willing to sacrifice a lot to live in a beautiful place.”

Niehaus was quick to point out that Moab’s public school system fits many students’ needs well, and being unable to accommodate neurodiverse students is “no fault of the public school. They’re just really limited in what they are able to do.” In Oscar’s case, there were obvious negatives to his attending the public middle school. Niehaus knew that he would ultimately be fine there, but he wouldn’t have opportunities to use his unique talents and learning styles to grow into the best version of himself.

“I really thought that there was a better way to learn,” Niehaus said. “I’m all about growth mindset.”

Sign up for Stand Together's K-12 newsletter and get stories, ideas, and advice from changemakers who are transforming education across the country.

That doesn’t just apply to Oscar. Setting out to start her own school also meant Niehaus had to stretch what she believed she was capable of. When she stumbled across the term “edupreneur,” her first instinct was to laugh. “I thought that was funny because I never thought I’d be an education entrepreneur,” she said.

Niehaus saw her lack of educational background as a strength, allowing her to think more creatively and openly about what was possible.

“I had never started a school, so I had no idea what I didn’t know,” she said. That eliminated many worries and left the path ahead open to experimentation. “I’m not afraid of trying things and failing.”

Niehaus’ first step, and what she advises for others looking to design education options, was to reflect on her own skills and talents and use them to guide her methods. In particular, Niehaus drew on the 15 years she had spent running an affordable housing nonprofit in Moab.

“I am not a teacher,” she said, “I am an entrepreneur. So instead of starting a homeschool pod where I would participate as the teacher, I started a private school where I could serve as the administrator because that’s what I’m good at.”

The same goes for those who are neither educators nor administrators: “If you’re a mayor or you’re a bartender or a landscaper or a data analyst … who knows?” she said. “I don’t think there’s any particular background — even educational background — that makes or breaks whether or not somebody could start a school.”

Thinking more broadly about what ‘school’ can look like

Niehaus’ road to starting the Heron School involved many dead ends, backtracks, and ongoing modifications — and she’d advise any other edupreneur to try all of the same routes she did.

Her first piece of advice: Don’t strike off alone, as she ultimately did. It’s better to work within the system. Before deciding to start an entirely new school, Niehaus approached the Moab public school system to see if it would be possible to collaborate using their resources. She also researched whether there were already schools in the area serving neurodiverse students that she could support rather than starting her own.

“I met with the superintendent, I met with some teachers, and I was like, ‘Is there a way that we could have a gifted and talented program? Is there a magnet school option?’” Niehaus said. In her case, the resources weren’t available, but for other edupreneurs, there may be opportunities to collaborate with others working toward similar goals.

Niehaus leaned into her background as an entrepreneur to think more creatively about how to secure a campus space. When looking at commercial properties available in Moab, a bed and breakfast with an available second building gave her an idea: She could use the space as a “profit for purpose” model in which she would partner with the B&B to raise funds jointly. This also helped with her issue of finding available educators — she could now offer housing to both part-time and full-time teachers.

“I was able to find an investor who was not scared of my crazy,” Niehaus laughed. “[They] felt the property was a good investment, so I was able to secure the place.”

Niehaus’ background as a nonprofit leader also came into play when it came time to design the curriculum for Heron School. When she began thinking about what the school would offer, she thought of those it would serve less as students and more as clients. She started by talking openly with the person she aimed to serve first: her son.

“I asked him, ‘All right, the public middle school seems like it’s going to be hard for you. What would your dream school look like?’” she recalled. “He painted a picture, and I said, ‘Let me do a little research and see if that picture is an attainable educational opportunity for you.’”

Oscar described characteristics like smaller class sizes, a flexible curriculum that would allow for deeper dives into specialized topics, and project-based learning styles. Today, all of these are hallmarks of Heron School.

While using the state educational requirements for core curriculum as more of a guideline than a goal post, students can home in on unique interests, like studying mythology to fulfill the English language requirement. When one student expressed an interest in poetry, Heron School hosted a poet who stayed at the bed and breakfast for 10 weeks while teaching classes in poetry and publishing.

After starting in fall 2022 with three students, Heron has since expanded to 12 students and two full-time teachers, with plans to hire a new full-time teacher for every six new students that enroll. However, Niehaus said, “Our statistics are not going to tell the story.”

It’s the satisfaction of students and their parents that means the most. Anecdotally, Niehaus has observed increased levels of attention and engagement, which she calls “counting smiles.”

As a parent herself, she is able to reflect on her own experiences with Heron’s first-ever student.

“My stress as a mom has decreased dramatically, and it’s not because I’m running the school,” she said. “[It’s] because my son is happy and my son enjoys going to school every day. That is the same metric that I [look for] with other parents. Is parenting easier because of our school? The answer that I get from all of them is, ‘My gosh, thank you so much for this opportunity because we were at our wit’s end.’”

For Niehaus, getting Heron School up and running was just the beginning. Her learning and journey as an edupreneur continues as the school itself grows. She recognizes that the needs and goals of her students will always be evolving — and so will her models and plans.

“I always joke that change happens as soon as the ink dries with a business plan,” Niehaus said. “If you’re going to be an entrepreneur in the educational space, you’ve got to be super flexible because you’re pretty much always putting new products on the shelf.”

Building Heron School from the ground up has allowed Niehaus to witness firsthand the transformation that using her unique strengths and skills as an edupreneur can have on 2e learners like Oscar.

“He’s a teenager, so he’s definitely on par with being like all other teenagers,” Niehaus said. “[But] he wakes up and heads to school on his own, ready and excited about learning.”

Heron School has also seemed to cure a curious illness among its students: “Whether it’s my son or the other kids at the school, there was a lot of ‘I don’t feel well today’ that kept them from attending public school,” Niehaus joked. “Now [at Heron], they’re all feeling so good. They all feel miraculous.”

Niehaus has worn many hats over the past few years — including mayor, nonprofit leader, founder, and edupreneur — but ultimately, she recognizes the core that has motivated her through all of it: a mom with a surplus of gumption.

“Don’t let perfection be the enemy of good,” she said. “That is my skill. I’m pretty good at things. It’s not a perfect school, and that’s OK because the alternative is a not-good school for all the kids. It’s a good school for some of the kids but not all the kids. I’m not going to stress about being a perfect school because there is no perfect school.”

The Heron School is supported by VELA, which as part of the Stand Together community supports everyday entrepreneurs who are boldly reimagining education.

Learn more about Stand Together’s education efforts and explore ways you can partner with us.

‘We want these boys to know that regardless of where they come from, they still can be excellent.’

This colearning space has the potential to bridge the divide between public and private education.

New Johns Hopkins data shows homeschooling’s recent surge has transformed the education landscape.

Step 1: Find the best learning environment for your child. Step 2? Figure out how to pay for it.