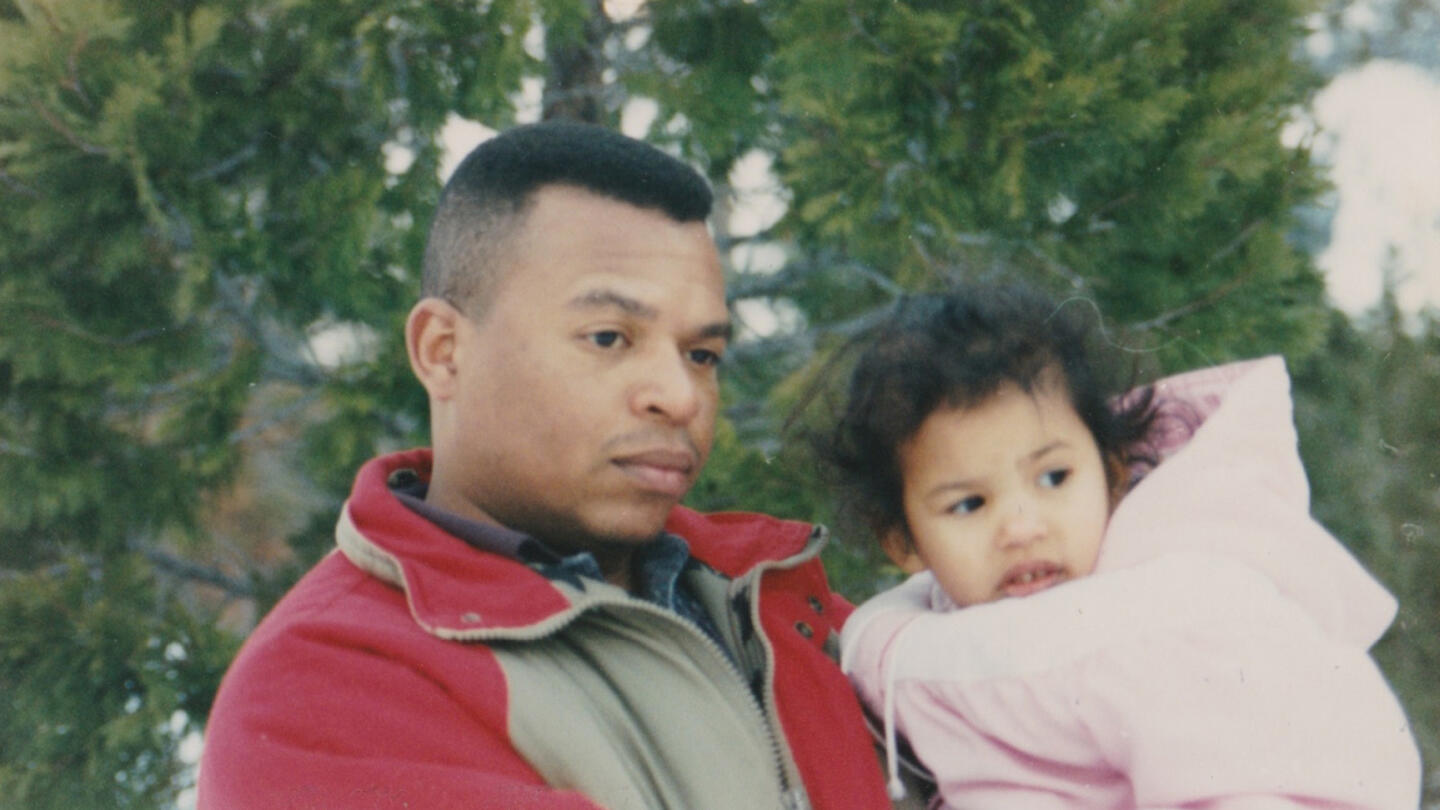

When Alyssa Tamboura was younger, she would tell people that her father had died in a car accident. It was easier than telling them he was in prison.

“There’s no shame in dying,” she said. “Everyone dies. It’s a condition of being human, but incarceration is different. There’s so much shame around it.”

At 11, Tamboura became one of the 2.7 million children in the United States with an incarcerated parent. As the youngest in her family, she didn’t learn about his 15-year sentence until he was already in custody. She never got to say goodbye, and her mother, struggling with alcoholism, refused to let her visit him.

Without emotional support, Tamboura coped with the trauma by pretending it wasn’t real.

“I processed it by shoving it down,” she said. “Denial was easier than facing the truth because facing the truth, especially without structured support at home, would have been catastrophic.”

In the United States today, more than 5 million children have experienced parental incarceration at some point in their childhood. Like Tamboura, many of them don’t have support at home, and studies show they are at greater risk for an assortment of negative impacts on their family lives, housing stability, mental health, physical well-being, and education.

For years, Tamboura’s story mirrored that of many children of incarcerated parents, but reconnecting with her father as a young adult changed everything.

While incarcerated, her father worked with The Last Mile, a nonprofit that teaches coding and software engineering to incarcerated individuals to prepare them for reentry into society. Inspired by her father’s growth and supported by The Last Mile cofounders Chris Redlitz and Beverly Parenti, Tamboura found renewed hope in her own potential. Today, she is a graduate of Yale Law School, having completed her education after dropping out of high school and while raising her son as a single mother.

What if we were better at supporting children of incarcerated parents — could we break the cycle of trauma and open doors to brighter futures, like The Last Mile cofounders did for the Tambouras?

As the shock of her father’s incarceration faded, so did the support

Tamboura uses words like “resentment,” “falling through the cracks,” and “invisible” to describe her childhood, but if there is one word that best captures the experience, it’s this: “Lonely.”

The day she learned about her father’s sentence, she found comfort from friends and teachers. Her mom had broken the news just as she stepped out of the car for school.

“I got out of the car, and there was a group of my friends standing around,” she said. “I was shocked. I walked up to them, and I just started crying.”

That day, her teachers, friends, and a school counselor were there to support her. But as the shock faded, so did the follow-up. She began feeling increasingly disconnected while her home life continued to deteriorate.

By her junior year, she had stopped going to school. A friend told her a teacher had asked about her. “Does anyone know where Alyssa is? She’s not coming to school,” the teacher asked the class. When students said they didn’t know, the teacher said, “Wow, it’s just a shame. She’s so smart.’”

“When I did go to school,” Tamboura said, “I never once remember this teacher pulling me aside and asking, ‘Are you okay? What’s going on?’ I think people around me saw me struggling but didn’t know how to help or couldn’t help. It was really just lonely.”

She dropped out of high school at 17, already a single mom. “By the time I had my son, I very much felt like a shell of a person that had no future.”

Her incarcerated father hadn’t abandoned her. She just didn’t realize it.

Tamboura’s dad had been writing to her from prison for years — letters, birthday cards, Christmas cards, all of which went straight into a box under her bed, unopened. He tried calling her, too. When she visited her grandmother, he would call hoping to talk, but Tamboura kept the conversations as brief as possible.

“I kept expressing that he’s dead to me,” she said. “He doesn’t exist.”

When she finally visited him as an adult, she expected her first visit would be a kind of reckoning. She pictured herself confronting him, accusing him of abandoning her, and blaming him for everything wrong in her life.

“I wanted to lay into him about what my life had been,” she said. “I wanted to ask him how he could leave me with my mom. How could he leave me and my siblings with someone who never should have been a mom?”

She went to the prison with her grandmother, who had forgotten to tell her father that Tamboura was coming. He had no idea she would be there.

“He came out into the visiting room, and I saw his face drop,” she said. “I walked up to him and before I could say anything, he hugged me, and he said, ‘I’m so sorry. I shouldn’t have left you. I take responsibility for how bad things got. I’m really, really sorry. Can you forgive me?’”

The two of them sat and talked and cried for hours on that first visit. When Tamboura went home, she pulled out her box of letters and read every one. She realized that her dad hadn’t abandoned her, that he had been trying to reach out for 10 years.

It was a turning point for Tamboura.

Sign up for the Stand Together newsletter and get stories, ideas, and advice from changemakers to help you tackle America’s biggest problems.

“Reconnecting with my dad was the thing that moved me forward in my healing journey,” she said. “I had built up so much resentment and anger towards him, and I pretended like he didn’t exist. It took 10 years to realize that my parent never gave up on me. It made me think, maybe I should find a therapist and talk through some of the things that I had experienced and how my father’s incarceration affected me.”

First, she went to her dad’s graduation — then he came to hers

After that, Tamboura started taking responsibility for her own life. She realized she could either blame her parents for how their choices affected her or make different choices for herself and her son.

She began to piece her life back together. She earned her GED, got her driver’s license, and started applying for better jobs — all while visiting her father in prison.

Her father earned an associate’s degree from Mount Tamalpais College in San Quentin — the only accredited independent college in the United States whose main campus is inside a prison. His was the first college graduation Tamboura had ever attended. Later, he joined The Last Mile, where he learned to code, worked as a web developer from inside the prison, and presented a capstone project to Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan.

“He just didn’t stop,” Tamboura said. “He continued to build himself up, and I kept thinking, ‘He’s doing all these programs. If he can do it, why can’t I do it?’”

Witnessing the positive impact of these programs in her father’s life made her realize that a better future was possible — not just for him but for herself. “The effects of programs like The Last Mile and Mount Tamalpais College trickled down generationally,” she said. “I was able to see the changes in his life. And I understood that a better future was possible, that I had choices and could choose my own path. Also, I wasn’t alone. I had people that cared about me.”

During this time, she became close with Redlitz and Parenti through her father and their daughter, Joslyn, whom she worked with at Stanford Medical School. They welcomed her as part of their family. She and Joslyn would go out to lunch and talk about their futures.

“It was one of the few times in my life that anyone told me I had a future and asked me what I wanted to do with it,” Tamboura said. “It’s so important when you’re someone like me who grew up with a lot of hardship or perhaps feels like your future is predetermined.”

She started taking night classes at the local community college, moved out of her mom’s house, and eventually attended the University of California at Santa Cruz.

“My dad came to my graduation with my grandma,” she said. “I can imagine the incarcerated parent; they see what their children’s lives have become in their absence, and it doesn’t feel good. My graduation was a moment for my dad when he realized, ‘Oh wow, she managed to be OK.’”

With mentorship from Parenti, Tamboura weighed her options when choosing where to attend graduate school. With financial support through a scholarship with The Last Mile, she went on to graduate from Yale Law School. Today, she works at a venture capital firm, serves on various nonprofit boards supporting children of incarcerated parents, and continues to rely on Parenti’s guidance as she navigates opportunities she once never imagined.

“What I have learned is that my fate is not predetermined,” she said. “I get to decide what my life is and what my life looks like, not the criminal justice system. I took back that power.”

“I have choices now. I didn’t have that before.”

The biggest difference between then and now? ‘How I feel about myself’

Drawing on her experience of growing up with an incarcerated parent, Tamboura is now supporting young people facing similar challenges. Put Me In!, a nonprofit Tamboura works with, provides grants for children of incarcerated parents to play sports through elementary, middle, and high school.

Being part of a team provides built-in support, something that could have made a significant difference for Tamboura.

“It’s a great way for kids with parents in prisons to build self-esteem, to be on a team, and to be around a lot of supportive adults that are invested in their well-being and their care,” she said. “It touches on everything: the emotional, physical, and spiritual well-being of children impacted by incarceration.”

Tamboura no longer hides behind the story of her dad’s “car accident.” She openly embraces her experience as a child impacted by incarceration.

The biggest change between her lowest point and her life now isn’t the stability and opportunity she now has.

“It’s how I feel about myself and my ability to handle the ups and downs of life,” she said. “When life is hard, I know that I have the skills, tools, support, love from others, and love for myself to push through it and come out on the other end a better, healthier, more whole version of myself.”

The Last Mile is supported by Stand Together Foundation, which empowers individuals to reach their full potential through community-driven change.

Mount Tamalpais College is supported by the Charles Koch Foundation, which, as part of the Stand Together community, funds cutting-edge research and helps expand postsecondary educational options.

Learn more about Stand Together's efforts to build strong and safe communities and explore ways you can partner with us.

How community leaders can get sustainable solutions that stick

We already have a key to reducing violent crime, according to this former law enforcement officer turned leading policy researcher.

The Frederick Douglass Project uses face-to-face conversations in prison to unlock possibilities for everyone.

About half of people leaving prison or jail will return. These five nonprofits want to change that.