At 10 years old, Kairi Ren Dionio is just tall enough to use her parents’ gas grill.

“I had to use my feet to tiptoe,” she said about grilling chicken to prepare her dad’s lunches for the week. “After that, I chopped up the greens and the vegetables and put them nicely into the containers with the tomatoes.”

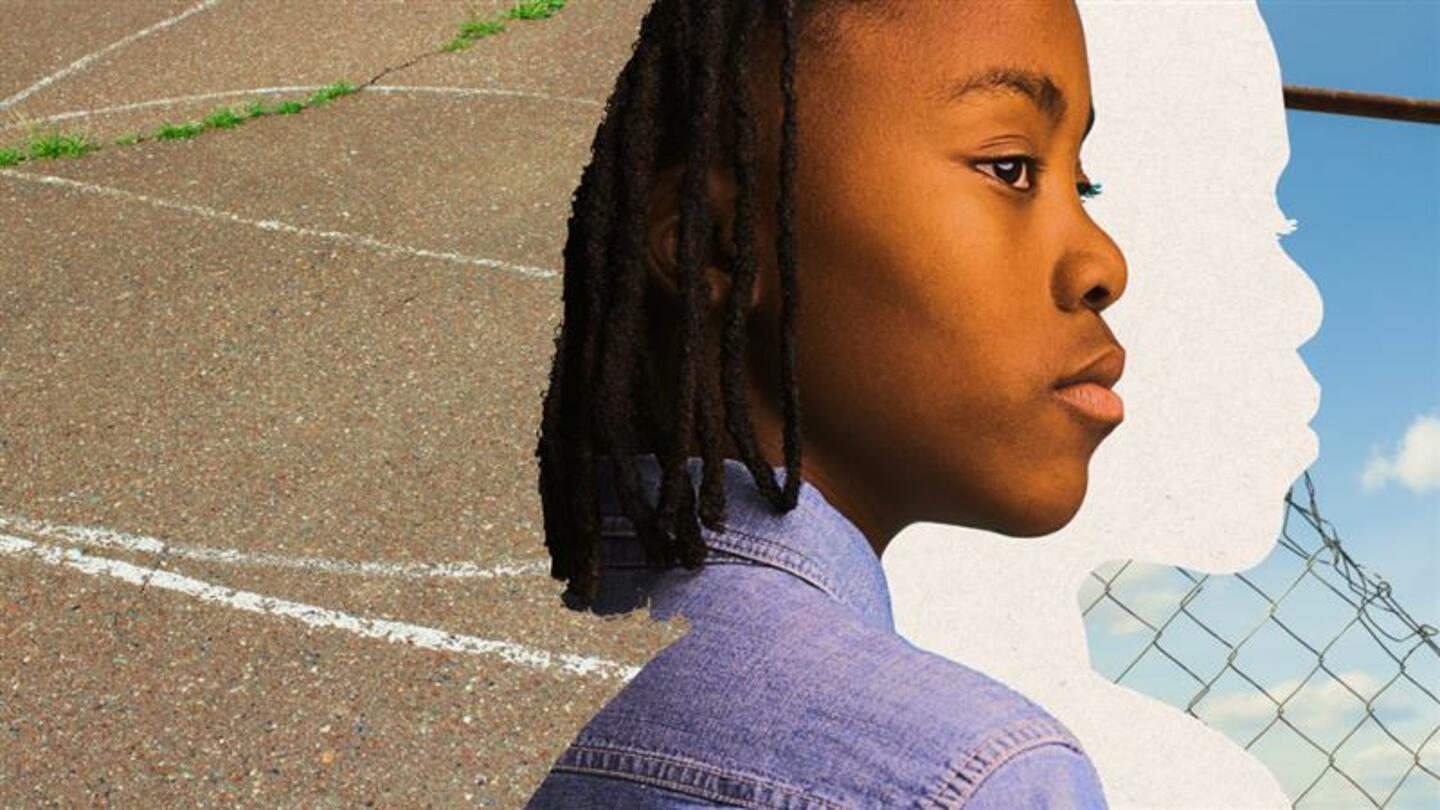

Kairi chose the task of making her dad’s lunches as part of a school assignment called “The Let Grow Experience.” The assignment is simple: “Go home and do something new, with your parents’ permission, but without your parents.” In other words: Parents can’t help students doing Let Grow projects. The assignment can be as challenging for parents as it is for kids.

“It was kind of daunting for me to watch her use a knife, use a grill,” said Janet Dionio, Kairi’s mom. “But as I watched her — I didn't help her — I could see how careful she was being.”

“Students have fewer freedoms than I did,” said Amy Wolfe, Kairi’s teacher. “It seems they have fewer freedoms everywhere but online.”

This is why Lenore Skenazy co-founded Let Grow, a nonprofit dedicated to helping parents “let go and let grow.” Once dubbed “America’s Worst Mom” by the media for letting her nine-year-old ride the subway alone in New York City, Skenazy and her co-founders Jonathan Haidt, Daniel Shuchman, and Peter Gray believe that today’s culture of fear and constant adult supervision is contributing to the mental health crisis among young people. It saps children of confidence in themselves and their abilities — providing an ample breeding ground for anxiety and fear. The solution? Skenazy says it's simple: Parents need to give their children more opportunities to be independent and explore their potential.

As Janet Dionio noted, this can be scary for parents. “It is hard to be the only parent doing any of this stuff, which is why we work through the schools,” said Skenazy. “We really feel like it's collective action that's going to change a collective problem.”

To some, this may sound great. To others, crazy. But what does this really look like in action? We spoke with two fifth graders and their mothers to hear how their Let Grow projects have impacted them.

Why parents need to let go and let grow

Children have less independence today than their parents did a generation ago. “I used to ride my bike around the neighborhood, and no one would know where I was,” said Nicole Austin, whose son, Zachary, has been doing Let Grow projects for Wolfe’s class. “A lot of parents talk about this, how we used to go off on our own. It’s a common sentiment.”

Skenazy explained that parents nowadays feel tremendous pressure to be a constant presence in their children’s lives. “It’s this idea that you can control everything,” she said. “If you pay enough attention, if you buy all the right devices, if you track and watch … and basically never take your eyes off your kid, then everything will be great.”

However, this constant supervision means children don’t practice independence. Without independence, they don’t learn self-direction or develop competence. When parents control the outcome, children miss the strength they get from moving forward even when something doesn’t go as planned.

“The problem is that we just don't let our kids do anything on their own,” said Skenazy. “We treat them all as if they're disabled and endangered and so fragile that if anything goes wrong, it will be permanent and horrible.”

Many children internalize these messages as personal deficiencies. If parents don’t believe in their capabilities and potential, how will they learn to do it themselves? Wolfe has seen this in her students.

“Students can feel unsupported and unequipped to act of their own volition … when they do not feel confident in their abilities,” she said. “This has the potential to create anxious and depressed youth in any demographic. Over the years, it seems like more and more students have been affected.”

Skenazy concedes that many parents have good intentions, but continuing this culture of fear and control makes it seem normal and OK, which is dangerous. “Dictators use fear and hate to get their way,” she explained. “So it's bad on an individual basis, and it's bad for a country — it's bad for democracy.”

Coming up with ideas is easy. Following through takes effort.

Each month, Wolfe introduces a new theme and the class discusses it. Then they brainstorm together about possible independent projects, though students ultimately come up with their own ideas.

For the theme, “Help your community,” Zachary Austin had an immediate idea for a project. “The one thing that popped into my mind was cleaning up trash,” he said. “So I thought, my school is pretty dirty.”

The idea was the easy part. He quickly realized there was a lot more to this project than just picking up trash. First, he had to figure out how he was going to do it. He decided to ask several friends to go with him to the school playground on a weekend and pick up trash, which meant he needed to work out how he would ask them. He made invitations for his friends, but then he had to determine the date and time and how to get the invitations to them.

“The idea, easy; asking people to come, kinda [easy]; and then once we're actually doing it, that's the hard part because once you have your idea, it sometimes doesn't go as well as you planned,” he said.

In this case, cleaning up trash wasn’t everything he expected. “I thought it was just gonna be normal plastic bags or pieces of candy wrapper, but we found really weird stuff, which kind of made it a little more fun,” he said. “We found three socks. We found a beanie, and we also found a doorstop. It was really weird, but I felt like I did make a difference. I did think it was a huge success.”

Austin has also baked brownies (both shopping for ingredients by himself and taking them out of the oven), cooked a T-bone steak for his family, and whipped up a batch of chocolate chip cookies. Next, he wants to teach other kids how to cook.

Nicole Austin found letting go challenging at first. “It was hard for me to not control all the little controllables,” she said. “Even like coming up with the ideas for projects — when he wanted to cook two times in a row, I wanted to lead him in a different direction.” But now she has noticed that allowing her son to do these projects has helped her loosen up a bit.

“We were at a soccer game, and there was a park way up on a hill, and [the kids] wanted to go play there while we're watching the other siblings,” she said. “[To the other parents] I was like, ‘They'll be okay. They can go and check in and come back, so just let them go and do it by themselves.’”

Now her son feels older. “I do feel a little different because if I didn't do any of these projects, I would still probably feel like eight years old,” said Zachary, who is 11. His mom said he is more inclined to challenge himself. He thinks other kids should do Let Grow projects. “I would tell them, hey, I think this would be really cool if you do it on your own so you don't have friends or parents telling you how to do it.”

Sign up for Stand Together's K-12 newsletter and get stories, ideas, and advice from changemakers who are transforming education across the country.

Kids need to challenge self-imposed and adult-set boundaries

The novelty of these independent projects — that they should be something the child has never done before — can be transformative. The task allows children to question both self-imposed and adult-set boundaries, essentially giving them permission to challenge their limitations.

When Kairi Ren Dionio made her dad’s lunches, she discovered she was more capable than she previously believed. “I thought I couldn't use the barbecue by myself, and then I never thought of using the knife by myself,” she said. The takeaway isn't about the barbecue or the knife. It's about this child realizing her potential to accomplish what she once deemed unattainable.

Other things she learned she could do: create a shopping list and budget, find the groceries at the store by herself, stay under budget, make crafts and sell them at a craft fair, decorate her parents’ car for a trunk-or-treat, and make a costume for her younger brother with things she found around the house.

Her preparation for the craft fair included two months of making necklaces, duct tape flowers, and Pokemon- and Sanrio-themed perler bead designs. But that wasn’t the hardest part. She said what daunted her the most was “starting to talk to people” — particularly adults she didn’t know.

“It was a bit nervousing because I didn't know them, and I wanted to please them so they'll buy my stuff,” Kairi said. Before, she had mostly stuck with her parents and teachers as the only adults she would talk to.

“I never really thought of selling by myself at a craft fair,” she said. And yet, about halfway through the fair, she realized talking to adults wasn’t so scary after all. It actually turned out to be fun — and she made $96. Next, she plans to 3D-print items and sell them at a booth at Comic-Con.

According to Janet Dionio, her daughter has always been an independent kid, but Let Grow has pushed her to question her limits and challenge herself. She’s also more mindful about what she’s working on. “Even with the crafting, she's more mindful of what she wants to sell and how she wants to sell it and how much she wants to price the products for,” Janet Dionio said. “She knows whatever the outcome, [she’s] responsible.”

Kairi creates a slideshow presentation about each project. It’s her mom’s favorite part. “She puts it all together, and you read it, and you look back, and you can see that sense of accomplishment — without the parent,” Janet Dionio said. “The look on her face when she accomplishes it. It's the best thing.” It’s a moment Skenazy hopes all parents experience more.

So, the big question for parents: “How do you dial [the fear] back?” Skenazy’s answer: Try it — start letting go.

“When parents see their beloved child do something on their own, then there’s this feeling of amazement, joy, and pride, and parents recognize that it means the kid is going to be okay,” she said. “It’s the only thing that provides any relief to parents and lets them let go again. So that’s why it may seem like a strange thing for someone to spend their life saying, ‘I have a homework assignment that's going to change the world,’ but I do, so that's it.”

***

Let Grow was supported by Stand Together Trust, which provides funding and strategic capabilities to innovators, scholars, and social entrepreneurs to develop new and better ways to tackle America’s biggest problems.

Learn more about Stand Together’s K-12 education efforts, and explore ways you can partner with us.

‘We want these boys to know that regardless of where they come from, they still can be excellent.’

This colearning space has the potential to bridge the divide between public and private education.

New Johns Hopkins data shows homeschooling’s recent surge has transformed the education landscape.

Step 1: Find the best learning environment for your child. Step 2? Figure out how to pay for it.