“Buy my mom a house, fix up my car, and live to be 24.”

These were the life aspirations voiced by 17-year-old Miguel, a high school student in Denver. A few minutes before, Kevin Byerley, who had been teaching Miguel and other students character development, had needed to kill some time. So, he asked them to write down three life goals.

“With where I came from, I thought it would be easy, but the kids really struggled,” he said.

At first, Byerely thought Miguel was joking. “You don’t really mean that,” he told him. “Of course, you’re going to live to 24.”

“No one in my family, no man, has ever made it past 24,” Byerley remembered Miguel saying. “Seven uncles, including my dad, have all been shot and killed.”

With that, the class went silent. Byerley was stunned. “All those kids resonated with [Miguel’s experience],” he said. Then he thought, “What is wrong with us that we’re okay with this? That at 17, a young man’s goal is to live past 24. It’s not OK.”

More than two decades later, Byerley is the CEO of Elevate USA, a nonprofit that works with middle and high school students in low-income areas to preemptively address community issues like dropout rates, substance use, teen pregnancy, criminal involvement, and homelessness.

“All of these challenges in a lot of these communities go back to the same root problem,” said Emma Turnbull, Elevate USA’s director of marketing and communications. “We call it relational insecurity or relational instability — not having that one person to confide in, to feel safe with.”

The organization operates leadership classes in low-income, urban middle and high schools, taught by full-time “teacher mentors” who share similar socioeconomic and ethnic backgrounds as their students. The class curriculum covers things like character development, conflict resolution, and integrity. Turnbull said the class is “like a springboard for deep relationships” between the students and their teacher mentors because of the conversations that follow each lesson.

The true impact happens after school and on weekends, when teacher mentors provide 24/7 support, fostering long-term, caring relationships. These mentoring relationships are healthy and stable, which is what many of these kids have been missing.

“Kids are just hungry for an adult to listen,” said Byerley. Over time, these stable relationships help students see their own dignity and potential, breaking down barriers and creating deeper connections.

“Early on, when we said that we build long-term, life-changing relationships, people would say that feels soft,” said Byerely. “But that’s exactly where all the outcomes are — having a positive, caring adult. Just one relationship in one of these kids’ lives makes the difference.”

Relational insecurity is at the root of society’s problems

Healthy relationships are critical. When children’s relationships with their parents or caregivers are unstable or unpredictable, they may learn to be wary and distrustful. When those relationships are abusive, they may internalize the abuse, sometimes believing they deserve it. Without intervention, the impacts can last into adulthood.

Child-parent relationships may be unstable for a lot of reasons: generational poverty, housing instability, parental mental illness or substance use, neglect, abuse, or domestic violence. The long-term effects of these traumatic experiences, commonly called adverse childhood experiences, are well documented. As many as 50 years later, the number of ACEs in a person’s childhood correlates with increased mental and physical health problems, substance use, poverty, unemployment, housing instability, incarceration, suicide attempts, and major causes of mortality.

Of the students served by Elevate in cities across the country, 60% don’t live with their biological fathers, 30% have moved homes in the last 12 months, and 35% skip school at least once a month because they feel unsafe.

Byerley and Turnbull emphasized that it all goes back to the relational insecurity caused by the ACEs. “These things that a lot of people are attacking are often symptoms of [relational insecurity], whatever that thing may be — whether that be dropout rates, substance abuse, teen pregnancy,” said Turnbull. “A relational problem requires a relational solution.”

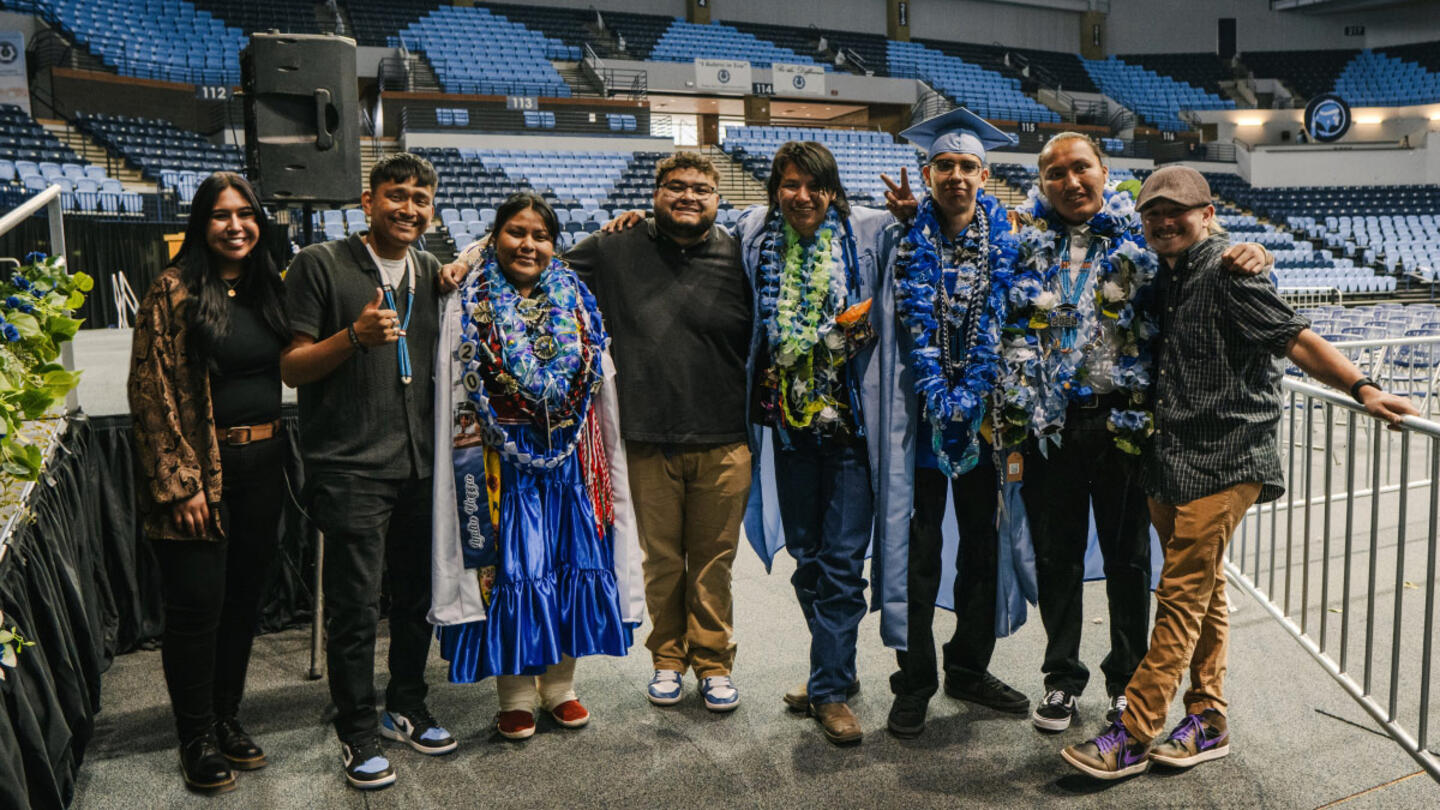

According to a recent report, building stable relationships with young people makes a difference. Elevate students exhibit improved character traits and social-emotional health after three semesters or more in the program: 91% of students are on track to graduate from high school after three or more semesters in the program, and 86% of alumni choose to pursue college, the military, or a trade school.

More telling are the choices Elevate students make in their personal lives. The number of them who choose to get out of bad relationships increases by 57% after three semesters, and they are more likely to become leaders, with a 167% increase in the number of students who report that their peers choose them to lead. Elevate students are also more likely to serve their community — 61% compared to the national average of 23%.

Sign up for the Strong & Safe Communities newsletter for stories, ideas, and advice from changemakers working with their neighbors to address the biggest problems we face.

No one gets there alone

The term “teacher mentor” means exactly what it sounds like: teachers who are also mentors. They spend time in the classroom teaching leadership and character development and time outside of school organizing activities and building stable, long-term relationships with their students.

If it sounds like a lot of work, that’s because it is. “We’re available to the students 24/7,” said Jacob James, a teacher mentor at Elevate Navajo. “We make sure that they’re healthy in all areas of life. That’s vocational, physical, intellectual, emotional, social, and spiritual.”

Teacher mentors’ primary responsibility is to provide students with relational stability — to be someone students feel safe with and confide in. This kind of relationship takes time, which is why teacher mentors make a long-term commitment. “Not only do we see students every day in school,” James said, “but we see them through every break between school, and then once they graduate, we’ll follow them into whatever life has for them afterward.”

“Relationships are huge,” he continued. “We like to say, ‘No one gets there alone,’ because we want our students to realize that they have people in their lives for a reason. Relationships aren’t there just to be there; those relationships all have a reason. Sometimes you just need a helping hand.”

For him, being a teacher mentor is a calling. It’s “something he can’t not do.” In addition to his love for young people, James is deeply devoted to his Navajo heritage and community. The Navajo Nation is grappling with significant issues: The number of single-parent households has shot up in recent decades, while fentanyl, alcoholism, domestic violence, and poverty are commonplace. When James was 10, the Navajo community he lived in experienced 15 youth suicides in a year.

He has noticed students becoming increasingly desensitized to these issues. It worries him, but he can see how students’ relationships with him and the other teacher mentors are helping them navigate their problems instead of pretending they’re no big deal. “Our time after school has really been able to help us deepen the impact and get to the root of some of the issues that these kids are struggling with,” said James.

One of the best places for building relationships with students is riding in the activity van. Teacher mentors open up about their struggles, which helps students feel safe opening up to them and each other.

“We have students that ask, ‘Can you drop me off last?’” he said. “Usually, when a student asks that, it’s because they’re ready to open up to you on a much deeper emotional level. So they don’t feel safe with everyone else being in the van for that.”

Parents also learn to trust the teacher mentors. It’s common, James explained, for parents to call on Elevate for help with their children. “Families are shorthanded because there’s only one parent in the home,” he said. “For example, there’ve been numerous occasions this year when parents call and say, ‘Hey, I’m still at work. There’s no way for me to pick up my student. Could you drop my kid off at home for me?’”

It’s good for the students to see that it’s OK to ask for help. “We teach our kids that vulnerability is not a weakness,” James said. “Nine times out of 10, when you open up about a struggle, there’s gonna be someone in the room that can say, ‘Hey, me too.’”

‘I didn’t even know I could do something like this.’

Once a week, Elevate high school students teach what they are learning about character development to fourth and fifth graders. James calls the program “Little Elevate.”

One of his students didn’t want to participate. “His first Little Elevate week was a disaster,” said James. “He was like, ‘I don’t want to ever go back in there. That was scary. Those kids are annoying.’”

The student did keep going, however — mainly because that was what his entire class was doing. After two semesters, he was calling them “my students” and getting emotional about leaving them for the summer. He told James, “I was shy at the beginning of the year. Now, I’m not shy. I don’t even want to cuss anymore. Those kids made me want to be a better person.”

According to Byerley, the Little Elevate program is a game-changer for the teenagers. “The high schoolers start to have some dignity for themselves,” he said. “They start to believe they have something to offer the world.” For many of them, the concept of being able to help others is new. “The most common phrase from the high school kids is ‘Gosh, I didn’t even know I could do something like this. You mean I can help?’”

At times, Byerley will ask alumni how they are doing compared to their friends who weren’t in the program. The answer surprised him at first. He expected the alums to be doing better than their peers, but it usually looks completely different. “I helped my friend,” the alum would say. “Most of my friends didn’t go that direction because I ended up bringing them along.”

Students who spend at least three semesters in the program have an average ripple effect of 12 people. Those might be peers, siblings, or parents.

James believes his students will become powerful Navajo leaders, “bringing change on a whole new level. We believe in them very dearly. I think that it is through investing in our youth that we can truly elevate the Navajo Nation as a whole.”

“We want them to be able to see their value and worth,” Byerley said. “Their value comes from who they are as human beings. That’s really fundamental for these kids to realize because sometimes it’s the first time they’ve ever heard it.”

Turnbull hopes the students discover how precious they are. “I think when they know that, the rest tends to fall into place, starting with breaking those generational cycles, doing it differently than what they saw,” she said. “I’d like to see them take refuge in themselves and have that self-trust and self-love.”

***

Elevate USA is supported by Stand Together Foundation, which partners with the nation’s most transformative nonprofits to break the cycle of poverty.

Learn more about Stand Together's efforts to build strong and safe communities and explore ways you can partner with us.

At this ‘resort,’ children with intellectual disabilities are seen as gifts to be celebrated and loved.

Veterans experience loss when leaving service. Could this be key to understanding their mental health?

The Grammy-nominated artist is highlighting the stories we don’t get to hear every day.

With his latest project, Blacc isn’t just amplifying stories — he’s stepping into them