On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that school segregation was unconstitutional. Yet 70 years later, in most major cities, schools remain segregated. In fact, segregation is growing in the nation's largest school districts.

Looking at school segregation since 1991, the Stanford Segregation Index found increased racial/ethnic and socioeconomic segregation. For example, Black-white segregation is up 35%, and segregation between poor versus nonpoor students has increased by 47%. Some estimates put current Black-white segregation higher than it was in 1968.

“Instead of segregating students based on race into classes — strategically saying, ‘Black kids go to this place, white kids go to this place’ — we now do it based on ZIP code,” said Denisha Allen, founder of Black Minds Matter, a network of Black school founders, activists, education leaders, and parents. “We still have a system of segregation. We just cloak it in a different mask.”

Some advocates are calling for a return to court-ordered racial school integration, but Allen said they’re focusing too much on the racial composition of the school and not the academic outcomes of students. “I think we got it wrong when it came to Brown v. Board,” she explained.

According to Allen, segregation and desegregation are two sides of the same coin. Both are forced choices — government mandating where a student can go to school based on factors only vaguely related to the student’s well-being. Allen has a better solution: Let families decide what is best for their kids. This means removing boundaries in public school systems and granting parents control over their children’s education funding, enabling them to choose the school that meets their children’s needs — whether public or private.

“The way that we can get to a better place is to allow parents to get their kids out of this broken system and go to a school that's going to best meet their needs,” said Allen.

School zones are historically discriminatory

As a catalyst for the Civil Rights Movement, Brown was pivotal. “Everything was separate and nothing was equal when [the ruling] came out,” said Allen. “We needed to specify in law that segregation was wrong.”

While the momentum of Brown took decades to fully manifest, the legal decision eventually contributed to widespread desegregation in the United States — banishing things like separate restrooms and water fountains, segregated public spaces and transportation, and restrictions on voter registration.

Education was a different story. Beginning in the 1920s, long before Brown, the federal government color-coded maps for urban areas in the U.S., classifying neighborhoods according to their mortgage risk. To this day, the practice has had devastating impacts on property values in minority and immigrant neighborhoods — most of them having been designated “hazardous” and unsafe investments for lenders. The practice, called “redlining,” was outlawed in 1968, but the divisions remain in how public schools are zoned.

“We still have the remnants of redlining because that's exactly how we zone for schools,” said Allen. Now, school zones are inextricably linked to housing and serve to reinforce neighborhood property values. “People choose where they want to live based on the performance of the school,” she said. It also means that, unless a person can afford to move, they are trapped by their income in the schools they can afford.

The end result is schools that don’t look much different than they did pre-Brown. “Today, predominantly lower-income households are minority households in Black and brown communities,” said Allen. “All of those students are being pumped into the same schools. Therefore, you have a system of segregation — one that was not formalized by race, but it definitely played out that way.”

Inequality between schools is apparent in physical learning environments as well as academic outcomes. “Only 15% of [eighth-grade] Black kids are reading on grade level nationwide,” she said. “You go to one district and you see that kids don't even have AC. They don't have heat in the wintertime, and in Baltimore, you have [40% of] schools with zero kids testing proficient in math.” Last October, a Superior Court judge in New Jersey mandated that the state address unofficial segregation in its school districts.

Diversity — it is and isn’t about race

According to a 2023 survey, nearly two-thirds of parents who are looking to choose new schools for their children are Black, and more than half of parents in urban areas plan to send at least one of their children to a new school next year.

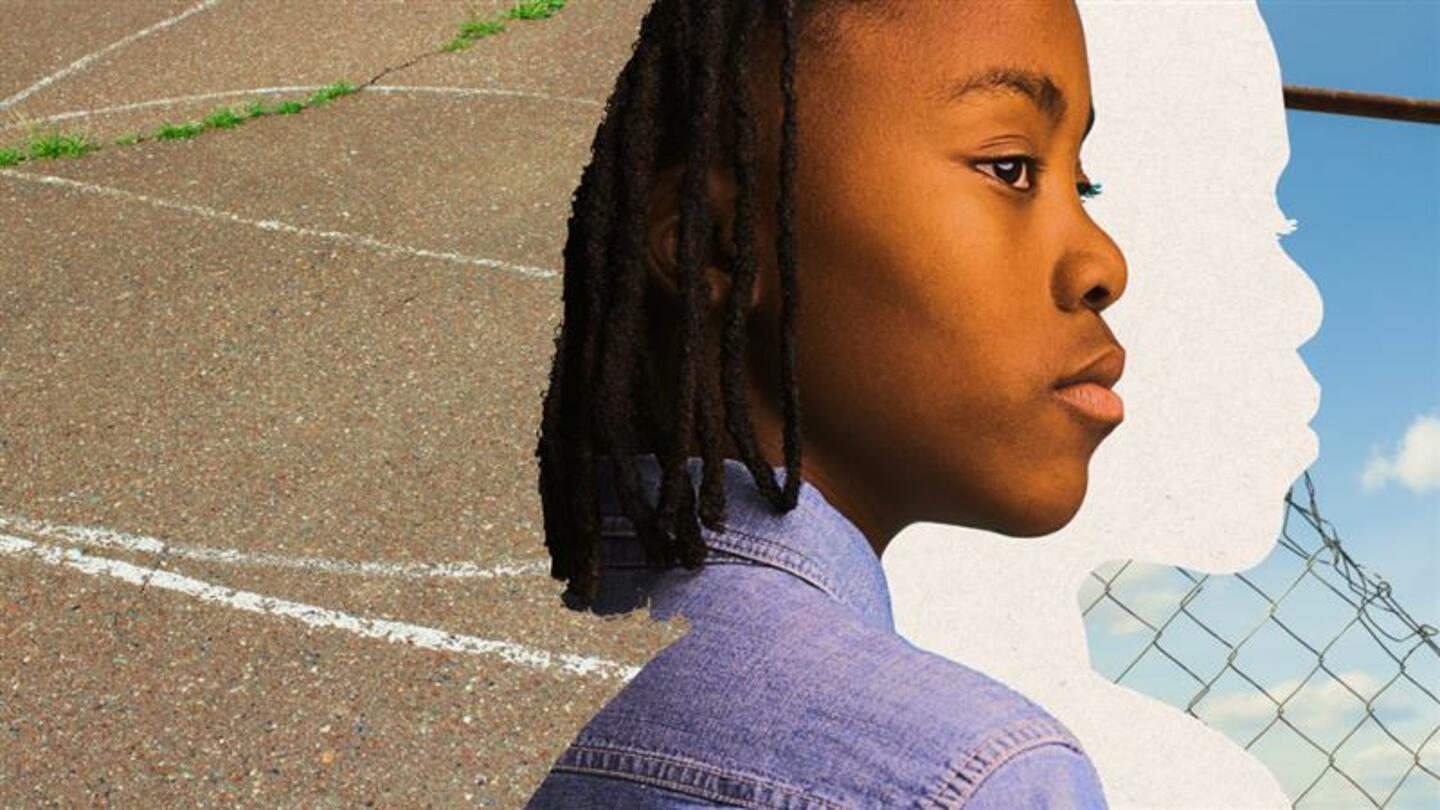

Allen grew up in a high-poverty Black neighborhood in Jacksonville, Florida, and went to a handful of entirely Black elementary schools. The uniformity of the schools she attended went far beyond skin color. “We were all poor,” she said. “We were all struggling in school. All of our teachers were stressed out. We all came from families that were broken.” The social problems of the neighborhood were concentrated in the local schools.

As a child, Allen responded to her environment by acting out. Picking fights with other students and teachers was a distraction to mask her feelings of inadequacy and a fast way to get out of class. “Now, looking back, I understand that teachers had a lot going on,” she said. “I was one of 30 kids who were all doing the same thing, who all came from the same background. [The teachers] didn't have the patience to really focus on my extra needs.”

Sign up for Stand Together's K-12 newsletter and get stories, ideas, and advice from changemakers who are transforming education across the country.

After failing third grade twice and cultivating a reputation for being a “problem student,” Allen got a tax credit scholarship to enroll in a local private school.

“I went from a school that was 100% Black with zero diversity to taking advantage of school choice at a school that was also 100% Black, but 100% diverse,” she said. “I was going to school with people whose parents were doctors. They were lawyers. They owned businesses — restaurant owners, groundskeepers. Just middle-class families who had jobs and stay-at-home moms. It was a very diverse student body. So when I came in with my own experiences, it was not like we were just putting flames to the fire. We were growing, trying to get better.”

Ultimately, we should be concerned about the academic outcomes of individual students, Allen said, not how many ethnicities or skin colors we can get into one school. “Whether they’re white kids or Hispanic kids or Asian kids or Black kids, no matter where they are going to school, they should receive a top-tier education. And right now that's not happening.”

There is more to life than the circumstances you were born into

In sixth grade, Allen didn’t immediately take to her new school. “I was still rebelling against the system,” she said.

One day, while she had in-school suspension, the teacher in the room asked her a straightforward question: “Denisha, what do you want to do? Do you want to go to jail or something?” Suddenly, this tough little girl who liked to pretend she didn’t care about anything broke down in tears.

“It kinda woke me up,” she said. “Like, what do I want? I know a bunch of people in my family who've gone to jail. It's like a badge of honor. … That was the moment when I said to myself, ‘Yeah, what are you doing?’”

At other schools, she had felt like she was one of hundreds of students, but not at this new school. “There were people every single day who were really concerned about how I was doing, not just, ‘She's acting out. Please send her to the office,’” she said. “It was a wake-up call. I was fighting people who care.”

Despite still being in an all-Black school, the people and environment gave her a new perspective. She didn’t have to act out in class anymore or follow the paths of her mother and siblings — none of whom finished high school. Jail time wasn’t inevitable like it had seemed before, and she didn’t need to continue fighting a system that made her feel insignificant and lost.

The biggest change for Allen? Hope. For the first time in her life, she realized she could aspire to more than the circumstances she was born into. Without the freedom to choose her school, the district boundaries around Allen’s neighborhood would have remained her whole world. Now she’s working to expand education freedom so that other families and young people can have that same hope.

“We are giving hope to families,” she said. “We are saying you don't have to subjugate your kids to failure.”

‘Every kid should be in a school that's going to work for them.’

Allen believes education freedom — the ability for parents to choose the best education environment for their kids — to be the civil rights issue of our time. “We're trapping kids into schools that just don't work,” she said. “If only 15% of our flights were operating successfully, we would not be okay with that. It would be really upsetting to people if 15% were the medical norm. The FDA would be shutting everything down.”

And yet, “we are okay with mandating that our kids go to school eight hours a day, and they are coming out not being able to read, not qualifying to go to college,” she said.

Currently, most states allow school systems to dictate who goes to which school. Giving the decision to families would be a major paradigm shift, making schools accountable to parents — not legislators — for student success. It would shift the focus from generalized metrics like grade-level percentages to ensuring each child gains the necessary skills for personal and academic success.

Parents would be able to choose “a great educational environment for their kids, one that's going to interest their children, one that's going to meet their needs and stick to whatever the parents value for their family,” said Allen.

It’s not just about poor-performing schools or even levels of diversity in specific schools. A high-performing school won’t be the best fit for every student, and only parents know what kind of environment will be the most helpful for their children.

“You might go into a school of choice, and it doesn't look diverse on skin level,” said Allen, “but you go into different stories, you go into socioeconomic status, cultural backgrounds, and you find that, wait a minute, these schools are extremely diverse. Parents are choosing these schools, not based on color, but on academic outcomes.”

“Education freedom is allowing parents to choose the best learning environment for their kids,” Allen said. “Every kid should be in a school that's going to work for them.”

***

Black Minds Matter is supported by Stand Together Trust, which provides funding and strategic capabilities to innovators, scholars, and social entrepreneurs to develop new and better ways to tackle America’s biggest problems.

Learn more about Stand Together’s education efforts and explore ways you can partner with us.

‘We want these boys to know that regardless of where they come from, they still can be excellent.’

This colearning space has the potential to bridge the divide between public and private education.

New Johns Hopkins data shows homeschooling’s recent surge has transformed the education landscape.

Step 1: Find the best learning environment for your child. Step 2? Figure out how to pay for it.