When Ayana Verdi’s 3-year-old started hating pre-K, she was surprised at first. Then, she got motivated to change it.

“Gio was inside at a desk, writing on worksheets for almost six hours a day,” said Verdi. When she asked his teacher for advice, the response was, “He just needs to understand that he can’t do the things that he’s going to want to do in school.”

Verdi was stunned. “She was telling me to get him used to compliance, get him used to shaving off those interesting pieces of himself because that’s school,” she said. Instead of changing Gio, Verdi wanted him to have an education that nurtured his talents and taught him to resist limits to his potential.

In 2017, Verdi and her husband co-founded Verdi EcoSchool, where the curriculum is a mix of traditional subjects, student-directed projects, and social-emotional learning. Their vision? To help young people realize their potential and build healthy communities.

It all sounded good. But a couple of years in, reality hit.

Verdi saw parents reacting to the uncertainty of being in an unconventional school in a self-limiting and self-defeating way. How could students learn to build healthy communities if their parents were modeling unhealthy behaviors?

“I realized we needed to consider if we as adults had ever learned to communicate in healthy ways,” Verdi said. She now asks parents to commit to intentional personal growth.

The result is a thriving school community where parents support each other and students are learning to interact in courageous and productive ways.

Parents often say they wish they had learned these skills earlier. What if more adults committed to their own social and emotional development? Is this something other schools and learning environments could try?

“I think it would change the world,” said Verdi.

Learning how to respond to challenges is crucial for children

After being disappointed by traditional schooling, the Verdis hoped a private school in South Florida would be a good fit for Gio. Unfortunately, that was not the case.

“It was probably more traumatic,” said Verdi. “This private school was trying to replicate the structure of a public school, just in a more beautiful setting.”

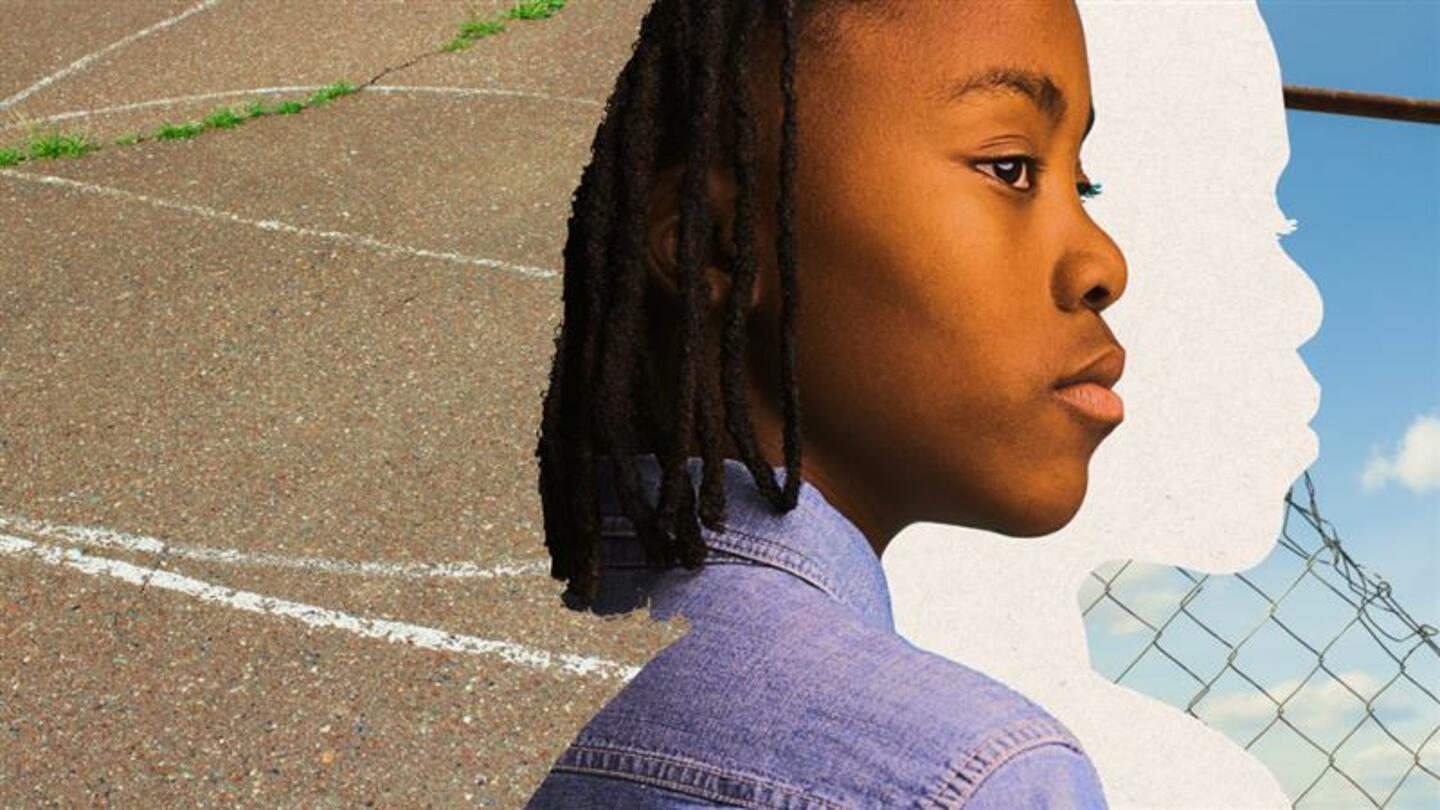

One day, Verdi walked onto campus during recess. She saw kids running around and playing, but she couldn’t see Gio.

She finally found him: “He was sitting in the grass, facing a fence that was maybe a foot in front of him while somebody kicked a ball into his back,” she said. “When I asked him what happened, he said he felt alone, that everybody was mean to him, and no one understood him.”

He felt like he would never belong at school.

That scene at the fence has stayed with Verdi along her school-founding journey. She doesn’t want him or any of her students to ever feel that alone. “I wanted him to know that he wouldn’t always feel that way,” she said. “There are times in our lives when we’re going to feel alone, and things are going to get hard, but there’s always a light.”

Verdi EcoSchool’s curriculum includes social-emotional learning — skills like self-awareness, self-regulation, and healthy communication. Verdi wants Gio to be prepared with these skills the next time he faces unkind treatment from others.

Jessie McCutcheon, whose two children attend Verdi EcoSchool, called it “learning how to be a nice human.”

Social-emotional skills also empower children to love learning and explore their potential by teaching them that they can choose how to respond to challenges and setbacks. “Those skills are at the heart of everything we do,” Verdi said. “When I pick up a book and can’t read it, I could throw the book or I could take a breath and ask for help. This is where we learn the skills to take with us for the rest of our lives.”

Teaching Gio these skills made sense because he was her son. Verdi could guide him in handling difficult situations both at school and at home. However, teaching other children presented a surprising challenge: their parents.

“I’ve had to learn that creating a successful trajectory for students and beautiful learning experiences has more to do with the relationships you build with families than the relationships that you build with children,” she said.

Sign up for Stand Together's K-12 newsletter and get stories, ideas, and advice from changemakers who are transforming education across the country.

Becoming a school family means showing up for each other — even when it’s uncomfortable

“No kid should live their experience at school with anything less than the ability to explore and make mistakes and make messes and practice,” Verdi said. “I think we as a collective community [society] have been doing the opposite for a long time. It is not safe to fail at school. Students are expected to know all the answers.”

“What happened to offering children a safe place to make mistakes?” she added.

Traditional education, which focuses on measurable outcomes and structured curriculums, can create chronic stress in children by teaching them that the world is made up of right and wrong answers.

However, for parents, traditional models may be the only kind of education they’re familiar with — which paradoxically can make innovative models feel less safe for them.

Education at Verdi EcoSchool looks very different from traditional schools that have desks facing a teacher with a checklist of things they need to teach students. Some parents weren’t prepared for just how different the experience would be.

The focus is on exploration and hands-on learning in an urban farm setting with 10 outdoor classrooms, a large garden, and a greenhouse. Students are organized into growth levels that span two or three years in age. Each morning, they set goals for themselves and plan their day. Classes include traditional subjects like math, English, and science, but educators make learning hands-on and relevant to real life. Students design projects to address real-world challenges, developing practical solutions and presenting their findings to the broader community.

A few years into creating the school, Verdi started to notice that many parents were having a hard time with the openness of this education model. They were fearful, wondering if this way of learning would harm their child’s future prospects.

They would come to Verdi with questions like, “What if my kid doesn’t graduate high school or go to college? What if they don’t find a good job because they went to this school when they were 7 and played in the dirt and planted some gardens? Am I ruining my child?”

These fears came out in other ways, too. Parents were having conflicts with each other over issues like curriculum changes and school policies.

During the pandemic, tensions worsened, with arguments over politics, conspiracy theories, and face coverings. According to McCutcheon, the shift to virtual interactions deepened the disconnect, as parents became more focused on their own concerns and less aware of other perspectives.

Since the pandemic, Verdi asks parents to commit to their own personal development. “We realized that to continue as a community, we couldn’t ignore the need for adults to do the work,” she said. “We had to engage in these skills and practices and interact in ways that would make us proud if we saw our children doing the same.”

Not only does the school community get together once a month to learn about communicating in healthy ways, but there is also a culture and community committee.

McCutcheon emphasized that connection within the school community fosters empathy. Knowing each other’s names, faces, and backgrounds makes compromise easier. “Even if something isn’t ideal for my child, I can better appreciate its importance for another child and their family because I know them,” she explained. “This understanding helps us work together to find solutions.”

Making these changes has been difficult, but it’s worth it. “Now this growth culture permeates our school family — with our children, educators, and parents,” said Verdi. “We’re all practicing shared language and shared ideas around personal development and how to show up for each other — even when it’s uncomfortable.”

“It has made us a school family.”

10-year-olds who can end conflict with a handshake and a hug

Since she began offering parents social-emotional skills, Verdi has seen dramatic impacts on students’ ability to interact in healthy ways.

“I have seen an incredible amount of growth in our students,” she said. “There’s a depth and maturity to them that is not typical.”

When Gio was about 10, Verdi saw him handle another incident involving a fence. This time he had the social-emotional tools to turn it into a positive experience.

A friend snatched something of Gio’s and threw it over the fence. After taking time to calm himself, Gio went to the friend and proposed they “rewind” the situation. It’s a social-emotional technique children learn at the school called the “time machine,” in which the two parties walk through what happened and how they could have handled it differently.

Verdi watched as Gio and his friend replayed the moment, each acknowledging what went wrong, imagining a better outcome, and ending with a handshake and a hug.

“We live in a world where people don’t want to listen to each other,” said Verdi. “They’re not interested in hearing someone else’s perspective or what they were thinking. It’s just, ‘You don’t agree with me. You did something to hurt me. You’re wrong forever.’”

“And here we had two kids who were willing to be present for each other and both accept some responsibility. In the end, they ran off, picked up a ball, and started a new game.”

“They’re growing up with skills we didn’t have.”

“If society focused more on nurturing each individual in our schools and gave them opportunities to practice communication and coping skills without stigma, we could change the world,” said Verdi. “Engaging parents in this work would increase empathy and willingness to see things from different perspectives.”

Verdi EcoSchool is supported by VELA, which as part of the Stand Together community supports everyday entrepreneurs who are boldly reimagining education.

Learn more about Stand Together’s education efforts and explore ways you can partner with us.

‘We want these boys to know that regardless of where they come from, they still can be excellent.’

This colearning space has the potential to bridge the divide between public and private education.

New Johns Hopkins data shows homeschooling’s recent surge has transformed the education landscape.

Step 1: Find the best learning environment for your child. Step 2? Figure out how to pay for it.