Northern Cass School in Fargo, North Dakota, may look like every other public school from the outside — but inside its doors, it’s pioneering a whole new way of measuring learning that could better prepare students for life after graduation.

In our last installment, we visited One Stone, a school that lets students direct their own learning. One Stone has seen huge success in molding more driven, focused, and fulfilled students, but there’s one glaring question: One Stone is a private school. Is the same model of flexible education possible within a public school?

According to Northern Cass, yes. The school serves 711 students — an entire school district. The difference? This school is making flexibility and choice accessible to public school students. Northern Cass has a 92% graduation rate, with 70% of its students going to college and 30% going into the workforce or military. How do Northern Cass educators explain their success?

“We’re looking for demonstrations of learning,” said Dr. Corey Steiner, superintendent at Northern Cass.

What does that mean, exactly?

“Taking a test used to be the end-all, be-all,” Steiner said. “It takes into account nothing about the real things that happen for a learner when they walk through our building.”

Instead, Northern Cass combines traditional testing with practical assessments that exhibit not just how well a student has retained the information but whether they can actually apply it to the life skills and career trajectory the student hopes to build. The result is an individualized pragmatic education model that directly supports each student’s unique talents and goals — all while meeting the requirements of the public school system.

The school’s model could hold valuable lessons on how schools of all types can make education more meaningful for every student.

Putting a new spin on traditional education

To be clear, Northern Cass still has tests — state law mandates it. Steiner teams up with parents and local lawmakers to include personalized education in the school while still adhering to the requirements of the public school system.

“We assess learning in a variety of different ways,” he explained. “If a kid says, ‘I don’t want to take the test; I actually want to demonstrate and have a conversation with you,’ we do that. We’re looking at a growth model.”

Steiner refers to this as the “studio model.” It allows students to choose their preferred method for demonstrating what they’re learning.

“The standardized test is just a small little sliver of their story,” he said. “We’re looking at the 98% of their story that gets written every single day with the experience they have here and outside of this building.”

Sign up for Stand Together's K-12 newsletter and get stories, ideas, and advice from changemakers who are transforming education across the country.

By definition, the studio model can look different for everyone. Students and educators codesign learning experiences, both parties making sure they meet specific goals and play to the student’s strengths.

Rather than telling students what to do, Steiner explained, teachers say, “I want to help facilitate that, not teach it. I’m not going to grab the information. You are going to lead that as a learner. When you’re going to get stuck, I’m going to step in, and I’m going to help.”

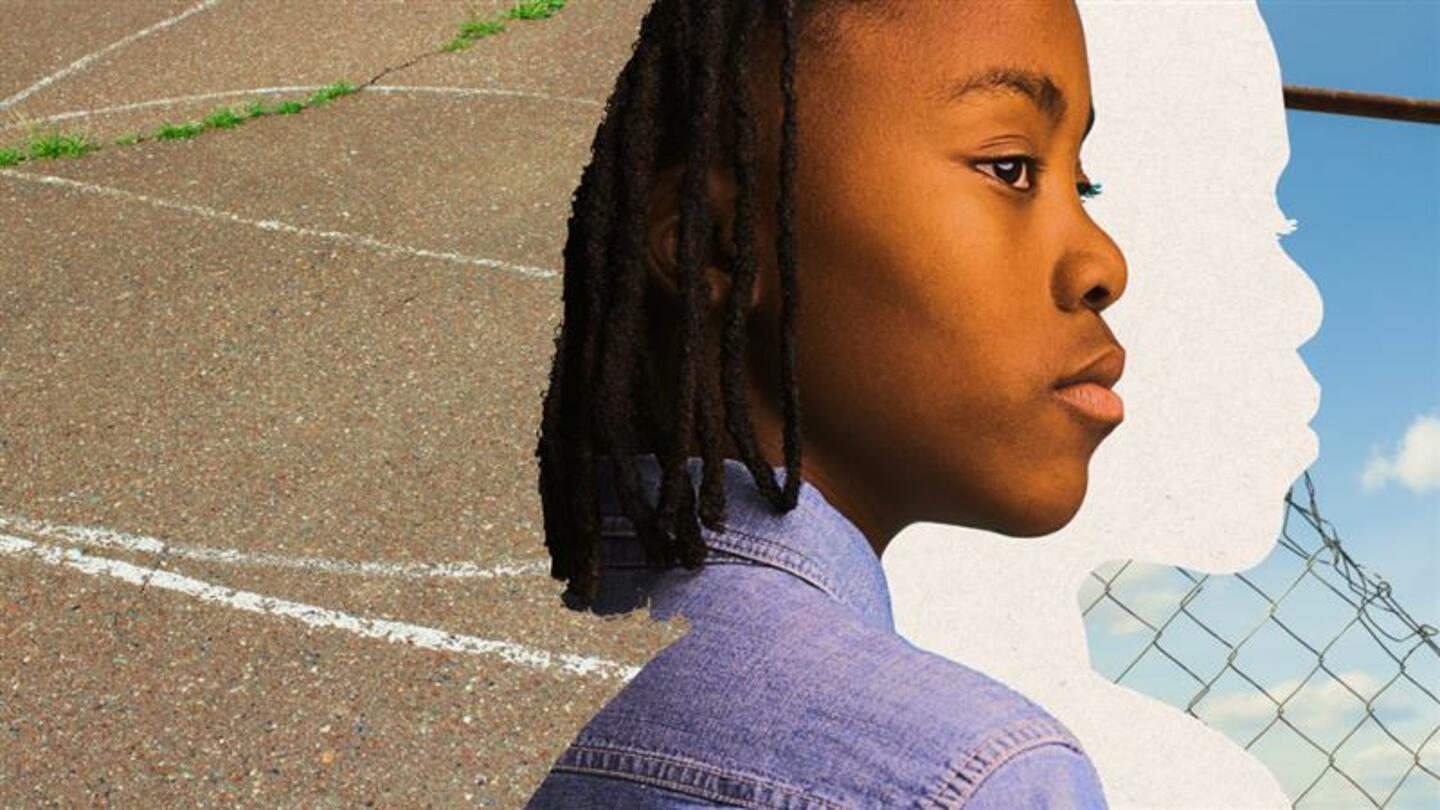

Maleah, a Northern Cass student, calls it “control over our own learning,” adding, “It means a lot to me because I don’t do well in standard structures. I don’t do well in classes where we have one homework sheet after another. But in studios and in personalized learning, I can take that more to my own interests.”

When students take required tests, educators can assess whether personalized learning helps or harms testing performance.

So far, combining personalized learning with state standards is working at Northern Cass. Students are performing impressively on state tests, outperforming averages in science, math, and English — proving that schools don’t have to choose one over the other. No single method is necessarily the “right” way to do education. When students are given choice, autonomy, and flexibility, they thrive.

“You’re still learning the things that other people would, but it’s not like, one fact, two fact, three fact,” Maleah said. “I’m going to be taught in a way that best suits me and what’s best for my interests.”

Lessons that students can use in real life

“We’ve given kids a lot of control and agency over their learning,” Steiner said. “A lot of places say they ask kids what they want to do, but not a lot of places listen. I think that’s one of the things that we’ve done a really good job of in our transformation. When kids say it, we listen because this is their place.”

Just ask Justin. Two years ago, he was considering dropping out of high school. He already knew what he wanted to do — take over the family farm and care for animals. He didn’t see how high school would get him there. His schoolwork just didn’t seem to apply to his future.

Then Northern Cass stepped up. Educators helped him reframe his curriculum to align with his interests and passions by including activities like welding horseshoes in his daily education.

However, Justin wasn’t only making horseshoes. He fulfilled his history requirement in a way that was relevant to his interests and applicable to his life — he researched the history of blacksmithing. For math, he created a business plan for the horseshoe-making business he hopes to start after graduation.

“This is what I’m going to do when I graduate,” Justin said. “I’m going to be a farrier. … This is what we’ve been working on for the last year, so when I graduate, I can go start a business.”

Pivoting education from being about standardized tests and grades to actual, real-life applications made all the difference for Justin. He has stayed in school and is deriving way more meaning and fulfillment from it than before.

“We recognize that every kid is different, and if you start with that in the forefront, you realize that the educational system has to honor that unique trait that every kid has,” said Tom, one of Northern Cass’ personalized learning coaches. “You can’t really make a cookie-cutter-style education to honor that. We try to offer as many opportunities for kids — chances for them to explore, find their interest areas and passion areas. They can really explore themselves and find who they want to be when they walk out of these doors.”

Whether public or private, education should serve the individual

“Our system’s not perfect,” Steiner admitted. “That’s the fun of it and sometimes the frustration of it.”

In a personalized learning system, he noted, there’s never an endpoint: With each new student that walks through Northern Cass’ doors, there is a new set of needs and goals to meet, requiring educators to continually evolve and adapt.

Despite the challenge, Steiner sees this as an opportunity. “It allows us to reframe what we look at when we see a kid sitting in front of us,” he said. “It’s not a percentage; it’s not a letter grade. It’s a human being.”

Whether in One Stone’s private, no-testing model or Northern Cass’ public, personalized-standardized hybrid model, both schools are demonstrating a fundamental shift possible at schools everywhere: asking how well education is serving each student’s unique trajectory and less about how well they meet predetermined standards.

Tests can have a place in education so long as educators support the individual students, recognize their unique skills and traits, and empower them with immediate feedback — in other words, what happens in real life.

“I don’t remember the last job interview I ever had where I had to take a test to get a job,” said Jun Campion, a One Stone coach. “Some of the shortcomings of traditional test-taking is that we don’t get to see the students’ whole picture. You get an isolated instance of where a student can pour out knowledge onto a piece of paper. That doesn’t give you their passions. That doesn’t give you their curiosities. That doesn’t give you any of their experience in life. That is what makes a person a person, right?”

Learn more about Stand Together’s education efforts and explore ways you can partner with us.

This piece is part three of a three-part series on school testing. Also see: Part one and part two.

‘We want these boys to know that regardless of where they come from, they still can be excellent.’

This colearning space has the potential to bridge the divide between public and private education.

New Johns Hopkins data shows homeschooling’s recent surge has transformed the education landscape.

Step 1: Find the best learning environment for your child. Step 2? Figure out how to pay for it.