Prison is never the starting point and very rarely the end point. The vast majority—95%—of currently incarcerated individuals will be released and attempt reentry to civilian life. The question Prison Fellowship asks is not what inmates did to get in, but who they will be when they get out—a question all of society has a vested interest in.

Making no excuses for criminal acts, Prison Fellowship prioritizes the deep work needed for incarcerated individuals to reengage with society positively and effectively upon release. They know that mistakes that define whole futures tend to follow lifetimes loaded with poverty, abuse, neglect, and all types of untreated trauma.

Familiar with their failures, detainees Amanda, Dawn, and Angelina say participating in Prison Fellowship Academy was their first chance to confront this underlying trauma and start healing.

"I have a long history of abuse of every kind and never really dealt with it," says Amanda, age 37 and five years into her sentence. "That's what brought me here. I heard a preacher say it's like a puzzle—people always start with the outside pieces because that's the easiest. And that's what it was like for me—I never put the inside together. I just swept all those pieces into the box. Not fixing the inside is what caused me to do something horrible."

An estimated one in three American adults have a criminal record.

"You cannot imagine what they lived through," says Pamela Page, Program Manager for Prison Fellowship Academy at Shakopee, a women's correctional facility in Minnesota. "The stories that I hear are gut wrenching, what happened in those young lives. Not all, but most. The skills, compassion, mentoring, leadership, parenting that wasn't there and many just need that. I haven't seen anything like that but the Academy."

While personal transformation is Prison Fellowship's highest aim and deepest impact, the subsequent benefits of that work to society are much broader and more clearly quantifiable. Take, for example, the fact that it costs taxpayers more to incarcerate someone in the state of New Jersey than it does to send them to Princeton for a year. And that's true not just in New Jersey but nationwide.

Prison Fellowship explains it this way: "Nearly 2.2 million men and women are behind bars, and more than 600,000 people are released every year—with two-thirds being rearrested within three years. The annual cost to incarcerate and reincarcerate this many people? More than $80 billion."

"The tough on crime movement led people to believe that we can just punish our way out of crime by incapacitating everyone—that's why we're the world's leading incarcerator. We're trying to help people understand that our more restorative approach is actually going to lead to safer communities."

Heather Rice-Minus

VP of Government Affairs and Church Mobilization

Prison Fellowship Academy is reforming to restore

Restorative reform begins on the inside with the shifting and shaping of prison culture. The hope, of course, is that correctional environments are as rehabilitative as they are safe and secure. All the data shows that if people emerge from prison utterly unchanged, then society will bear the burden of their incarceration more than once. This is not only a financial flush but a human drain as well, as children are raised apart from parents and achievement potential goes unrealized.

"The biggest challenge is trying to get people to understand that we aren't forgetting the victims in this whole process. In no way are we trying to excuse behavior, we are just trying to prevent it from happening again," says Tracy Beltz, Shakopee's warden for the past eleven years.

While the insides of correctional facilities can be night and day different from city to city, state to state, the warden always sets the tone. Recognizing this, Prison Fellowship engages wardens like Tracy in an exchange program where they share experiences, challenges, and support.

"I am ultimately the one that is responsible for setting the tone, ensuring that mission is carried out," says Warden Beltz. "And our mission is about crime reduction and safe facilities and those things go hand in hand. Continuing to make sure that people understand that, it's huge, it's everything."

At Shakopee, Warden Beltz has been a strong proponent of and leader in modeling restorative reform. "It's easy as an officer, for example, to get locked into safety and security," she says, "But their jobs are so much bigger and so much more important than that. The way that they interact, the way that they hold offenders accountable, the way they encourage them when they're doing the right thing, those things are so significant to our women's ability to get out and stay out."

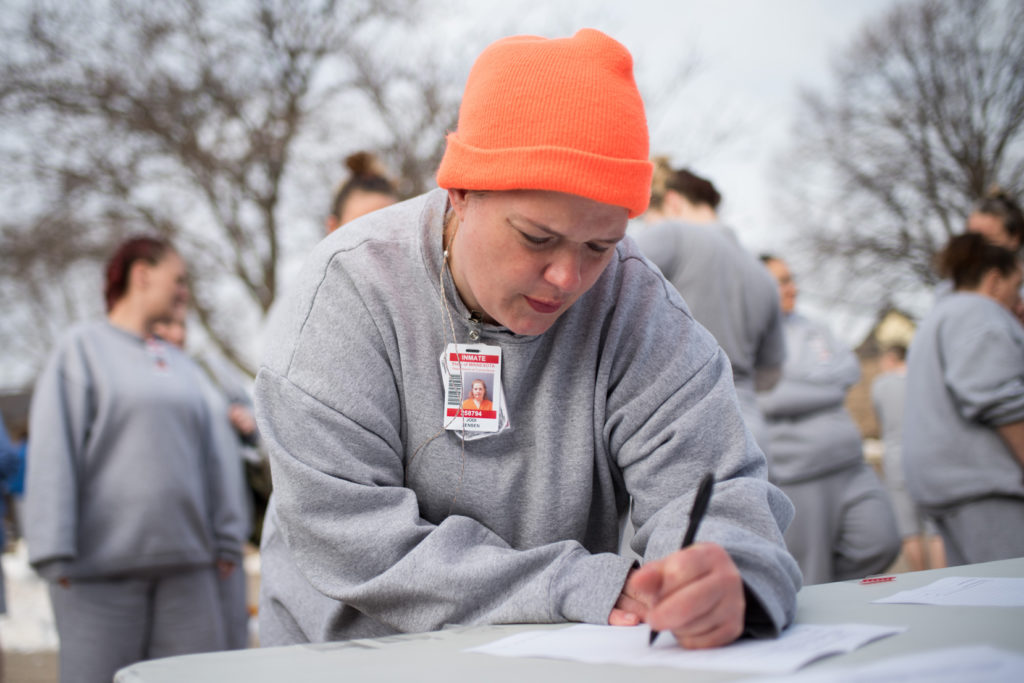

While wardens and prison staff facilitate the inside space, Prison Fellowship staff and volunteers work to build a supportive outside world of improved welcome. For example, in 2017, Prison Fellowship declared the month of April Second Chance Month, inspiring dozens of other organizations, leaders and states to do the same—Minnesota among the first. This is where the annual Second Chance 5K started, too, involving both the incarcerated and the surrounding community.

"The Second Chance 5K does a couple of things," says Warden Beltz. "First, it's about promoting positive culture. The inmates start seeing things differently. They start seeing the light at the end of the tunnel and see that it's not just them in this fight. There are other people that are supporting them—they know people are running on the outside for them. It supports a positive culture going forward and that's what we want. We want to see them get out and succeed."

Dawn, age 50, stands in front of her peers as a keynote speaker at the race: "For me and the depth of my destruction, it took me that whole year [in the Academy] to really process and forgive myself and work through all of that shame, guilt, regret, all of that stuff. I love me now."

Once a very broken spirit, Dawn was honored by Mrs. Page's invitation to speak at the rally, leveraging her pain for someone else's gain. "That's kind of where my heart is," she says. "If I get the opportunity to talk to women about that self-hatred that we carry, or to women and men with eating disorders. It was over a 38-year battle for me, so to be free from that is amazing."

"Accountability is a huge piece in the change process," says Warden Beltz, "But the reality is that if they continue to do what they did to get in here, they're going to continue to create more victims. So, being sensitive to the fact that there are people out there that have been victimized, we are just trying to prevent it from happening again."

Collateral consequences

Even for very changed and deeply restored people like Dawn, those coming out of prison will need to persevere for the rest of their lives—overcoming thousands of collateral consequences as they pursue higher education, apply for loans, buy homes, coach their kids' sports teams or volunteer in their classrooms, and perhaps most challenging of all, find work that builds to livelihood and career. And this is not only for the individual, but whole families working to repair after time served—even those proven innocent.

Now point person leading Returning Citizen Affairs for the DC Mayor's Office, Brian Ferguson was a college student with plans for law school when he was arrested and wrongfully convicted of a homicide is 2002. He was sentenced to life in prison without parole and sent to a maximum security prison in West Virginia. Once he got pro-bono representation from one of the biggest firms in the country, they were able to find the responsible individual, his case was overturned and Brian was released—but that was eleven years later.

"Everyone who's either been incarcerated or been close to people who are incarcerated knows that the family goes through it just as much, if not more," Brian says. "The feeling of loss, of having somebody ripped away from you and not being able to do anything about it is very traumatic, and they haven't done anything in all cases, right? That was probably the thing that most bothered me about my incarceration was the impact that it had on my family, especially on my parents."

Similarly, during a Prison Fellowship panel discussion about the church and community's role in criminal justice system reform, Georgetown associate professor of law, Shon Hopwood, says, "We tend in America to think that when we impose a long sentence on someone we're just punishing that person, but that's not true. I mean, the family goes through the punishment just as much as the defendant does. And all of the social science data tells us that it impacts kids the most."

Before becoming a professor, Shon robbed five banks in his early twenties and consequently spent eleven years incarcerated. "Reentry was challenging in so many ways. I had never been on the internet. I had never seen an iPad, an iPhone, an iPod. One of the first things I realized when I was trying to find a job, was that employers don't advertise in the classified section of the newspaper anymore. I got to the half-way house in the fall of 2008, probably the worst time to come out of prison. No one was finding work, let alone the guy that had committed five armed bank robberies."

All of the social science data tells us that it impacts kids the most.

The challenges are immense, which is why Prison Fellowship engages whole communities in the effort to restore the incarcerated and build opportunity for the healing of individuals, families, and the neighborhoods they belong to. From hosting sports programs and holiday events for affected families to inspiring neighbor initiatives (like the Second Chance Community 5K) that prime communities for welcome and home.

In different ways, Dawn, Brian, and Shon each embody this central Prison Fellowship conviction of compassion and concern for those coming behind them. Those who endure and are restored invariably take on the mantle of hope-building and change-seeking on behalf of those still broken, still behind bars, or still adjusting to life on the outside. It's a restorative and virtuous cycle powered by the soulful work of Prison Fellowship, which believes in the dignity of every person and the importance of second chances.

"When crime happens it tears the fabric of the community. We want to see that individual held accountable, but also have opportunities to transform, make amends, and really earn back the public's trust."

Heather Rice-Minus

VP of Government Affairs and Church Mobilization

Free on the inside

Back at the state prison in Shakopee, rooms designed to house one woman often house two, and meals need to be taken in shifts. We see the restorative work begin with Prison Fellowship's academy program here, which is twelve months long, broken up into quarters with a new cohort beginning every three months. Women entering the program come from many different places, but generally, I'm told, nobody trusts each other and nobody particularly likes each other. The culture of prison can be highly judgmental and tribe-oriented, relationships laced with distrust.

"From the very beginning, we're teaching skills to have healthy relationships and starting to prepare them to grow these relationships through the course of their life," explains Pamela. "If you talk with some of the women who graduated from our program and are on the outside, they'll talk about how difficult it is to find that inner circle again. And we certainly don't want women coming back to prison to be a part of our program."

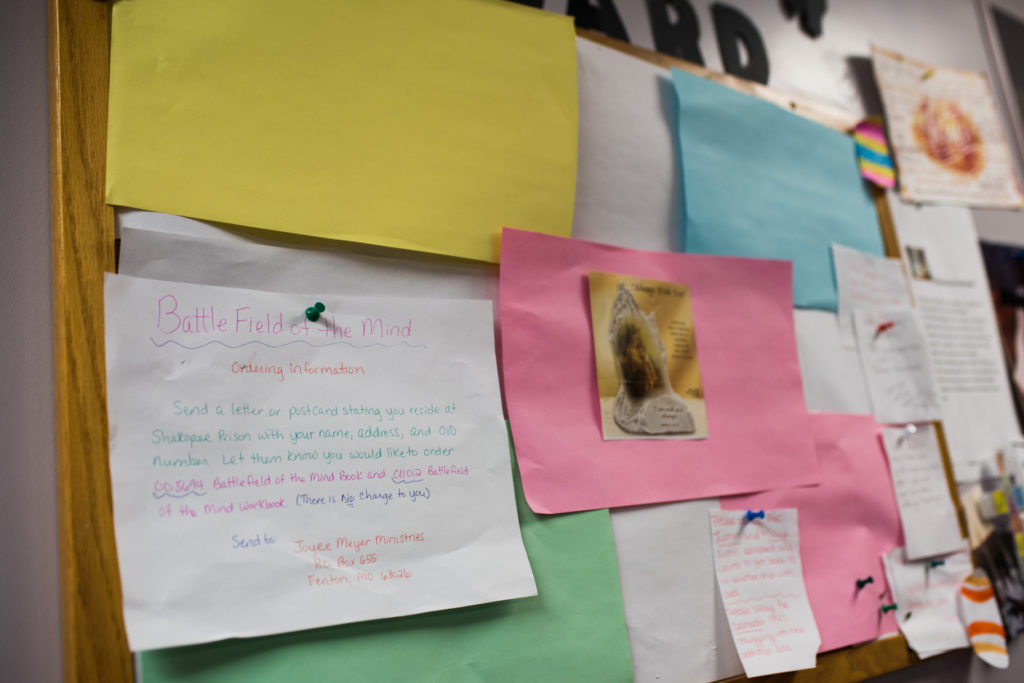

Classes take place in common rooms with a white board at the front and tables in clean rows, with six blue plastic chairs neatly tucked around. Each spot has a handmade name card with "Ms. Lastname" on it personalized with flowers, crosses, hearts, and other doodles. On another wall, community, integrity, and respect are glued on in big letters above a table-sized corkboard carrying pastel prayer requests. With pink and blue flowers taped to the door, the room is bright and rather peaceful, an oasis with deep breath spirit.

The first quarter centers on core values and team-building, helping the women participants—which is about ten percent of the population incarcerated here—bond as a supportive group. Early lessons in managing emotions are critical, for women overcoming a variety of destructive emotions, like anger and fear. Participants can also elect to go through Alpha, a curriculum studying the basics of Christian faith.

"I was lost when I came here. I was so discouraged. Through the program, I found my strength. I found out how to be more assertive, to stand up for myself. It's life-giving, and life-changing."

Annette, Age 50

Prison Fellowship Participant

This foundational emotional work is followed by relational skill-building, like boundaries. The women learn how to communicate and maintain healthy boundaries, a necessary step preparing them for lifelong relational repairing.

"The third quarter is very difficult because here we're going really deep into thinking distortions," says Pamela. "At this point, they are doing presentations about victim stance and blame and all these things. Because now they can recognize it and they're strong enough to say, 'This is where I've been, but that's not me anymore. I don't want to go back to that.' Really I think the key healing takes place at about nine months…that nine-month mark is where we see people start feeling free on the inside."

Finally, during fourth quarter, the focus shifts to preparing for leaving and life on the outside, including a class on overcoming offense and another on life management.

"We love the women who are in this program. While it's somewhat formal in nature in instruction because it needs to be, it needs to be structured and somewhat formal, there's room for absolute warmth and tenderness and compassion," says Pamela.

"Being here has saved my life. Through Prison Fellowship I've taken that time to put the inside of the puzzle together. Without this opportunity, I never would have paused and done that. It has saved my life."

Amanda, Age 37

Prison Fellowship Participant

The long way

A PFA mentor, Angelina is serving a 198 year sentence. "I was in abusive relationships and I was really broken," she says. "I felt defeated. I felt a lot of sorrow. I felt shame. I felt guilt. Now today, I have an identity. I feel strong. I feel courageous. I know that I have a purpose to help walk beside other women and be there for them so that they know that they can live a different life and do it differently."

"She's here for a long time, so she sees herself mentoring the other women who come in. She loves to cook. She's created a cookbook and she wants to get it published. That's her piece, and she serves on other committees within the prison. That's our expectation—if you're part of the Graduate Leadership Program, you're going to be impacting the whole prison."

Pamela Page,

Program Manager for Prison Fellowship Academy

"I've been in PFA for eight years now. It's been very impactful—life changing, life-giving. Before, I was broken, had no self-esteem, no identity. Now, I am a woman who is redeemed. I have an identity. I have worth. I am free."

Angelina, Age 46

Prison Fellowship Participant

For those nearing the last half year of their sentence, volunteer mentors work alongside participants to create a release plan. Once on the outside, the same mentors follow up by phone and in-person meetings to ensure support is maintained, particularly in the first several months of adjustment.

Prison Fellowship also supports returning citizens by advocating for policies, like expanded educational opportunities, that offer pathways for successful reentry.

"Education plays a huge role, not only for people once they come home, but for people within the system," says Brian. "Education is really the key to a lot of people's advancement, and I don't just mean on the academic side. I mean, trades. I mean being certified in things that are going to be able to allow people to be self-sufficient and have a sense of pride for themselves, for what they're able to do and contribute to society, to their family."

"I know of very few people I was in prison with who wanted to get out and commit new crimes. We know what works. From here on out, it's not a matter of what works, it's the political will to actually change the system and make it better for everyone," says Shon.

"We not only have to bring the hope of our faith to individuals, but the gospel actually calls us to confront injustice. We have to be not only about changing individuals, but also changing systems. That's actually our call."

Heather Rice-Minus

VP of Government Affairs and Church Mobilization

***

Learn more about Stand Together’s criminal justice efforts and explore ways you can partner with us.