Their debt is too high. Their credit is ruined. They have the fewest skills, the least English, the highest number of criminal convictions, a history of addiction, or any combination of those. They might have physical and mental health problems. Their children might be sick.

Miraculously and consistently over the past 30 years, Homestretch has seen the adults and children of those same families become nurses, teachers, accountants, chefs, commercial drivers, business analysts, realtors, mortgage brokers, and pastors. Referred the most challenging cases and achieving unparalleled outcomes with zero reliance on government funds, Homestretch is a purple unicorn if ever there was one.

We are proving that the people seen as least likely to succeed can completely upend expectations, including their own.

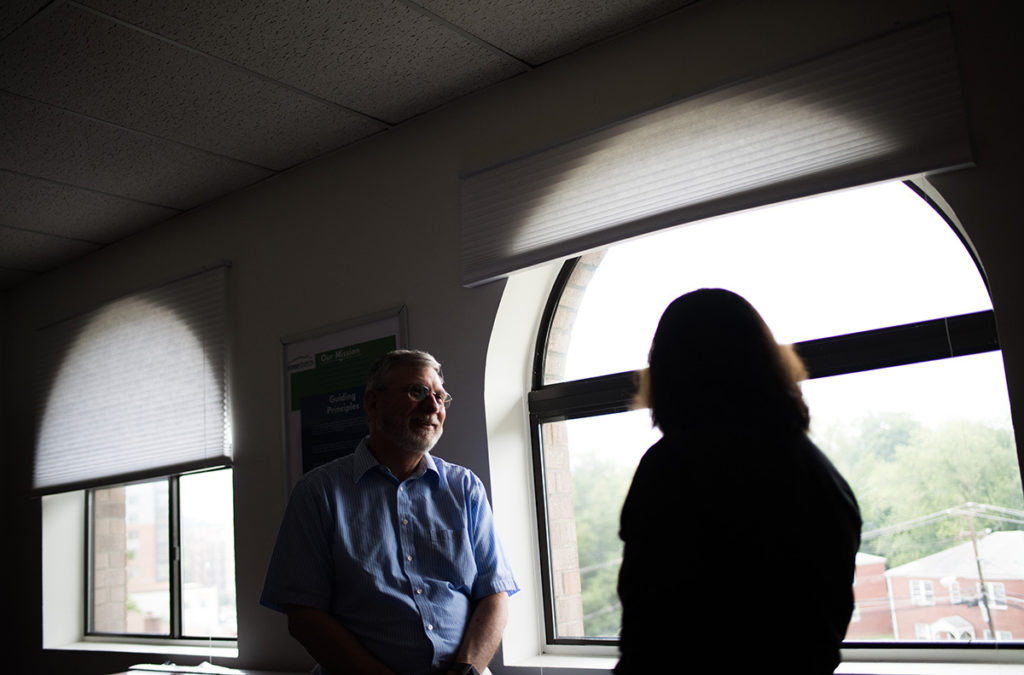

Christopher Fay, Executive Director

It comes down to the fact that Homestretch is focused on self-sufficiency, not housing. Long-term, getting people rehoused into situations they can't afford is not success. No thirty, sixty or ninety day metric will tell you if you've actually ended homelessness for a family. That truth will be told years later, but these questions and timelines aren't ones many service providers want to be held to: Three years after intervention, are families able to maintain market-rate housing on the income they earn? Has their income increased and debt decreased since their engagement?

In the realm of ending homelessness nationwide, Homestretch feels strongly that the vast majority of government-funded programs are not measuring success this way. The common, deep issues that cause homelessness, usually related to trauma or disability, are factors not quickly solved with new keys.

"In the world of homeless services across the United States, it is my deep belief that they are measuring the wrong things," says Ken Bradford, director of community outreach and resource development. "If you're not looking at increasing income, if you're not looking at reducing debt, you're looking at the wrong things. Because if you don't do those two things, you're not going to be able to be stably housed on your own—with or without a voucher, actually."

90% of Homestretch participants graduate and 95% of graduates are still housed and employed two to five years later

Christopher Fay, executive director of Homestretch, goes further: "The ultimate goal with each of these families is to get to the point where they no longer need TANF, they're not going to be on Social Security, they're not going to need any type of subsidy. Those things are all valuable in the short run, but it's not the end goal. The end goal is to make more money, become a homeowner, pay your way. So, we help them acquire the skills so they can achieve those things."

Believing that solving homelessness for a family has a lot more to do with wholeness than housing, when a family joins the program they are immediately relocated into one of Homestretch's fifty apartments peppered throughout Fairfax county, Virginia, and two years of transformative care begins.

We really hold to the idea that people are capable. That's fundamentally one of the things that differentiates us from everyone else. We believe in the capacity of people to change the course of their lives in powerful, dramatic ways.

Christopher Fay, Executive Director

Motivations

Dwight, who's proudly seven (not four or five or six), sits in his living room as his mom, Brandy, dives into their story. College educated and employed full-time with the United States Postal Service, Brandy checked in to the Patrick Henry family shelter in Fairfax with toddler-Dwight in tow.

She was referred to Homestretch on account of the kids and the domestic violence they all endured. "I was 300 pounds then," she laughs incredulously, showing proof on her phone

"Most of the people we serve are women. It's not exclusive to women, but 95% of our adults are women and 90% are single mothers," says Christopher. "One of the things that hold them together, despite whatever they went through, is this desire to protect their child and to see that child have a future. They may have given up on themselves, but they haven't given up on that child. And so, that's what we build on—that hope."

The average age at Homestretch is nine-years-old.

Asked what got her through Homestretch's rigorous two-year program, she smiles and says, "There was a woman, Soneli Bhadra, I looked at her as a mom. She had this temperament that was just like water. It never changed, never wavered, and that was what allowed me to trust that process—her unwavering."

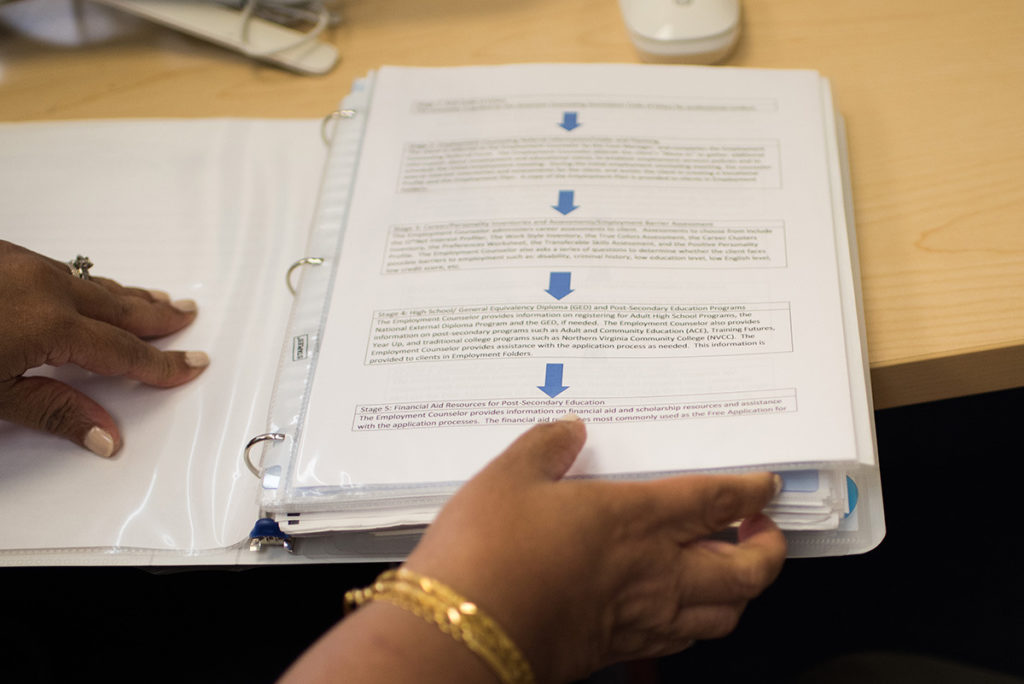

Soneli Bhadra is the Employment Manager at Homestretch and has been coaching people through employment barriers for 20 years. "My role is specifically to help each individual determine what type of educational and career path they can take that would be accessible to them, achievable, and short-term, so that by the time they are done with our program they can come close to, or are at, self-sufficiency," says Soneli.

Decades ago, she got into coaching and employment counseling for adults with disabilities so she could figure out how to help her sister, Sonya, keep a job. Sonya, was five years older, kind, generous, and 'much less spicy,' Soneli says, but she had a disorder that caused grand mal seizures. "They were big and dramatic (she would get knocked out), but she didn't injure other people," says Soneli. Still, each time Sonya had a seizure, she got fired. "It happened at three different federal jobs and two private jobs. And I got angry. Her coworkers, her friends, everybody saw that she was a great employee—I couldn't figure out why having a seizure would change that," says Soneli.

In the years since Sonya passed away, Soneli has become a fierce and fiercely loyal advocate for those who might need a bit more understanding and unconventional support to become self-sufficient.

"Maybe now it's not for Sonya anymore, it's for everybody else that I've seen get treated unfairly. I don't want to think that another family has to see their loved one pass and not have the opportunity to have that quality of life that you get from having a stable job that's so core to who people are."

Soneli Bhadra, Employment Manager

Like Brandy. Today, Brandy is a certified yoga instructor, 127 pounds slimmer and a whole world lighter. She has started her own business, Soul Good Kitchen, and is learning to play the guitar.

"I'm used to working with people with high barriers, helping them achieve their vocational goals," says Soneli. "Right now we are working with many people with significant criminal histories involving violence or drug charges, as well as people with cognitive disabilities, whether it's from a developmental disability or a brain injury or substance abuse."

Homestretch also works with many people who have very low English levels and large family sizes, where language proficiency and the cost of childcare are significant barriers to education and employment.

It's how we grow as a society. I see my role as being part of building communities. Once our clients achieve self-sufficiency, they can start supporting themselves, get off of government assistance, and start purchasing goods and services, paying taxes, paying into the community, which supports the next group of people who need this kind of service.

Soneli Bhadra, Employment Manager

Solving poverty

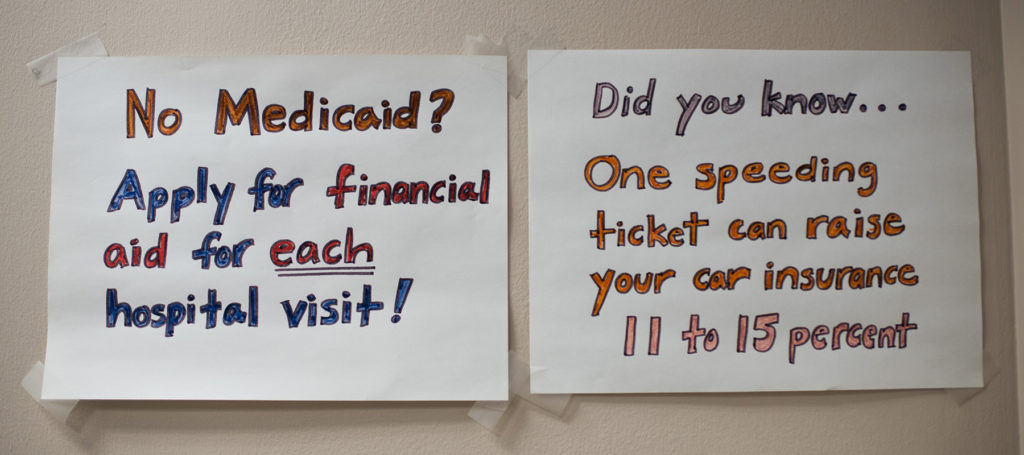

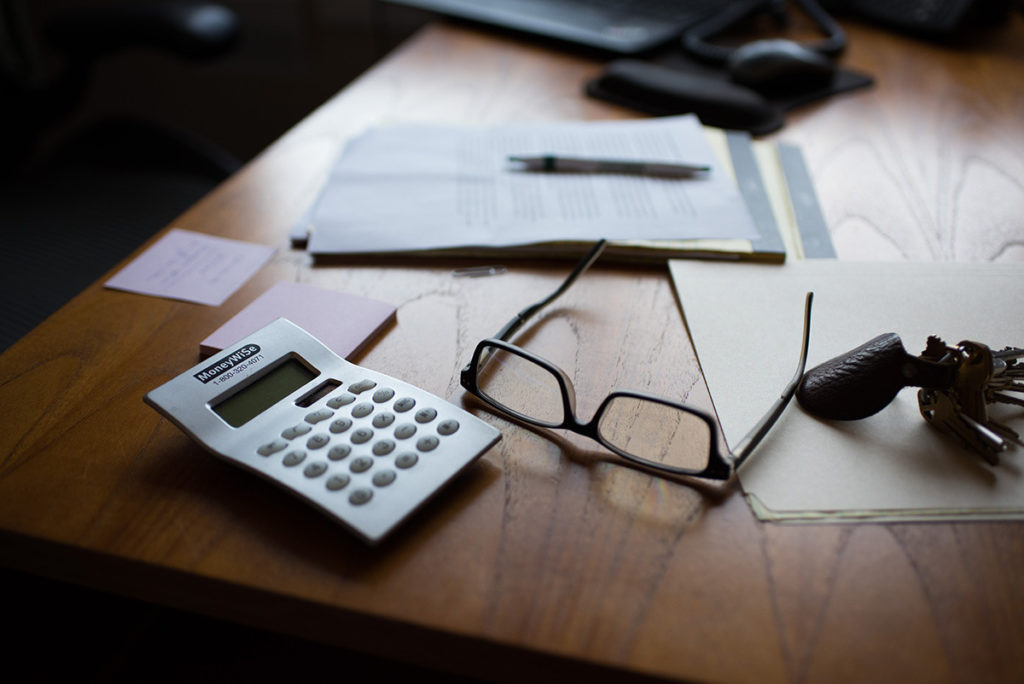

Entering with different magnitudes of need and priorities, every family at Homestretch begins in Heather Lynskey's office reviewing their finances and credit report. Heather is a legend, like a Mother Teresa of money management issues and budgeting for the poor and vulnerable. For 16 years she has helped clients repair or establish their credit, set financial goals, create strategies, and renegotiate heavy debts.

Getting right down to it, Homestretch has developed some mandatory financial requirements that serve as guardrails of success. For example, individuals must: 1. Save 10% of their monthly gross income in a Homestretch custodial savings account, 2. Have their taxes prepared through Homestretch with any tax refunds committed to paying down debts, and 3. Contribute 30% of their income to rent (which is really just another savings account). The discipline of maintaining those ratios is key to ensuring long-term self-sufficiency.

"It's hard. It's a lot of money to give up," Heather sympathizes, "And I know it's hard for them to do that, but when the clients start to see those debts being paid off and that savings accumulate, they get excited and all the pushback goes away. Now they're into it."

Because housing debts tend to be very large and rather old, it's not realistic for families to just pay that off over time, so Homestretch uses their tax refunds to negotiate settlements. "Another thing I'm looking for is student loans. Student loans are a big issue. And unfortunately, it's almost always from for-profit schools and often, the client left the school without even getting a degree, but they run up a lot of student loan debt," says Heather.

Over the past six years, about three quarters of our families have come to us with heavy debt load—on average about $8,000. About 80% of our families then leave the program with about $4,700 in savings. Even in a high-cost area like Northern Virginia, that's generally enough for the first month's rent, the security deposit, and living expenses.

Heather Lynskey, Credit Counselor

"Everyone's had different barriers and they've often had trauma, so there's a period of building trust. But when you see that they're starting to trust us and trust the process, they're getting excited and they're making progress, that's everything. That's the reason we're here," says Heather.

In rhythm with Heather's debt reduction strategies, Soneli beats the increasing income drum. To start, Soneli listens to clients' journeys and helps translate abandoned dreams into new goals. Along the way, she coaches them on work skills like communication and self-esteem building and professionalism in the workplace.

"Everything that happens with the family hinges on the employment process," says Soneli. "Without the income, or without the education to eventually see that type of income, nothing's going to change. It is absolutely core. That's why there's so much pressure to get the goals written quickly and everybody on board. And, of course, the financial part and the housing part are also integral."

Within just a few weeks, Homestretch families will have working budgets drafted and baseline goals set. "We can't waste a minute. Every minute is filled. And even then, two years is a tall order," says Soneli.

"Solving homelessness is really solving poverty," says Christopher. "Our clients are extremely vulnerable, accustomed to loss and disappointment and despair, and being lied to, broken and hurt. Trusting again, trusting some stranger with their lives…it's an incredible privilege to be able to do that for somebody."

Claudia Flamenco was one of those somebodies. Though just 13 years-old, Claudia married for love and moved with her husband to America in 1999. A year later she was pregnant and beaten regularly—more than once pushed from the top of the stairs to the basement below. Several years later, when her baby daughter grew old enough to understand and experience the violence herself, Claudia fled. A social services provider helped her find shelter at a motel for the first week and then referred her to Homestretch.

"I had bad credit because of my divorce. Homestretch taught me how to save money and with the skills class, taught me how to talk with professionals. Being in an abusive relationship, you have a lot of issues, like stress and depression, but I feel like everything that you ask here, they treat you like family," says Claudia.

Over the three years that followed, Claudia attended all the Homestretch classes, saved money, went to school, earned a degree in accounting, and bought a house. "My first job was at Giant—that was my first job out of the house. And then I went to Costco, and then I started in insurance with State Farm," she says. "I was lucky that I always had a good boss who would teach me."

When she bought her house, her loan officer recruited her to be his assistant. After a year, she decided she wanted to become a loan officer herself—and that's what she did. Now six years later, in a beautiful full circle moment, Claudia recently helped secure a loan for another Homestretch family buying their first house right around the corner in Falls Church. "That felt good," she says, smiling and putting it simply.

Kidstretch

With all of this, it's shocking to remember that the average age at Homestretch is nine-years-old.

"When the general public hears the word homeless, or thinks of a homeless person, they're not thinking of a child, they're not thinking of a family," says Kim Baker, director of Kidstretch. "With our programs, we start with meeting the needs of the youngest—trying to get them excited about school, excited about their afterschool activities, getting them engaged so that we can break the generational the cycles of poverty."

Kim has been with Homestretch for 14 years and in that time, was the one to start Kidstretch, a state licensed preschool program owned and operated by Homestretch. "We opened Kidstretch in August of 2012, specifically to help the three to five-year-olds who are in the Homestretch program, though we're also open to the public. We do have some families coming in from the community, which is a nice balance," she says.

With new families joining Homestretch, Kim often spends a good bit of time and energy trying to educate Homestretch families on the importance of early childhood education, because all the data shows that kids who are in preschool are less at risk to drop out later in high school. Intentional and professionally-trained educators play a vital role in how whole families overcome homelessness and end the cycles of poverty for good.

"I was interning as a case manager working specifically with the adults to help them set goals, and a lot of those goals were centered around their children—how they were parenting, how they were getting their children to school, what they were doing about childcare. I found that one of the big things that was lacking for these families was finding affordable, high-quality childcare or preschool programs," says Kim.

LaSharen Howell, a Homestretch graduate and now board member, remembers this well. Her daughter, Maya, was just three-years-old and her son, Alex, was in middle school when the family entered the program: "It's very isolating to be a kid in a home that doesn't have what they need, while still trying to be a kid and make people feel happy and make sure mom sees that you're happy or that dad and your sisters and brothers are okay or not scared," she says.

There's a lot of growing up prematurely that happens to kids that come from homes with domestic violence or sick parents or people who are underpaid and overworked and they never see their parents and they've got to pick up their little sister from school and make some dinner and do their homework and still get good grades, not be a sassy mouth and do their chores.

LaSharen Howell, Homestretch Graduate

"A single mom who has experienced domestic violence is not going to trust anyone else to care for her child," Kim explains. "So it's breaking down those barriers of, yes, we are someone that you can trust. We're going to nurture your child. We're going to take care of them and love them like they're our own."

Practically, that means being consistent and deeply caring, setting clear expectations and maintaining routines that build stability and security in the classroom, and later, in the home.

"Following rules and routines is a big focus because, as I mentioned, their schedule has probably been a little unpredictable," says Kim, "so we want the children to learn when you enter the classroom you wash your hands, you sit down, you get to go play, then we're going to have morning snack and it goes through the whole day. It's something that they can rely on and count on."

For the even littler, when parents meet with their credit counselor or go to life skills class on Wednesdays, babies and toddlers are cared for by Norma in the nursery drop-in center. "Norma is there, who is a grandmother-like figure. People love to see Norma—she is a legacy around here," says Kim.

We see this as the very first opportunity for the parents to collaborate with educators. We're hoping to set the stage for what's going to be—hopefully—very positive home-school connection and interaction. For some of the parents it can be anxiety producing because maybe they themselves had a horrible school experience, maybe their parents didn't get involved in their schooling, or maybe they were in and out of schools themselves.

Kim Baker, Kidstretch Director

For the older-than-preschool youth, Homestretch runs programs offering an incredible range of activities, organized in part by Emma Ryanmiller, Youth and Family Program Coordinator: "We help them enroll in school and find transportation. We sign them up for summer camps. If they need ESL help, they get ESL help. We do a lot of evening programming, like guitar lessons and cooking classes. On Mondays, they meet with a tutor. We just did an Operation Backpack, so every kid got a brand new backpack with all the school supplies they need, and school clothes and shoes. In the fall, they'll get new coats. At the holidays, they all get presents. If they want Christmas trees, they get Christmas trees. On Thanksgiving, every family gets a Thanksgiving Day meal. We find adopters to fund all of this and I organize all of it."

LaSharen saw the difference the multi-generational support made for her family: "With my son, Alex, it was rough because he was in middle school, so he was old enough to know about all the stuff that was happening. He was there in the middle of it, but Homestretch provided him with counseling all the way through the ordeal. He loved Ms. Jaclyn and all the kids. He was very active in whatever activities they did. I think part of it probably helped inspire his love and passion for cooking because that's what he does now."

Today, Alex has joined the US Coast Guard, and in her capacity at Deloitte, LaSharen helps organize her office to get bicycles for every Homestretch kid for the holidays: "I think giving a kid a bike is kind of giving them independence but it's also letting them be a kid still and just have some fun. It gives them some hope and a sense of accomplishment, just to be able to learn something new and to be free."

Scaling

With thirty years experience and lessons learned, Chris believes the organization could double its reach in Fairfax and also begin replicating the model in other communities.

Imagine the difference this would make to single mothers like Kenisha, a young woman with seven kids ranging in age from one to twelve. Kenisha had a high school diploma, but no work experience because she had always wanted to be a mom—that was her dream. She fell in love, got married, and had seven kids. When the abuse became unlivable, she found her way to Homestretch.

"We realized in order to help her we would need to help her find some career path that was substantial [salary-wise] because of the number of kids she had. We finally got to the point where we said, 'When you were a little girl, what did you dream of becoming?' Her eyes lit up. She said, 'Oh, I wanted to be a nurse. Always wanted to be a nurse.' So we said, 'Well, what if we could make that a reality? Would you want to go for that?'"

And they scoped it out together—figuring out timeline and tasks, like what kind of time she'd need to study adequately, how much support she'd need for the children, what kind of transportation, tuition, etc. "It took her three years, rather than the typical two, but in three years her income went from zero to about $90,000. And of course, that's a field where she can add certifications and work anywhere—she can go anywhere in the United States and work as a nurse."

"Kenisha's kids, especially the older ones, saw their mother struggle," says Christopher. "They knew what it was like to live in a shelter. They also saw her work really hard and achieve something that she might otherwise have thought was never within her grasp, and feel the joy of that achievement."

With these types of outcomes and rates of success, why don't others do it this way?

"I actually believe that it's because we don't believe in the capacity of the poor. Society tends to consider the people at the bottom rung lost and we don't want to make the kind of investment in them that it takes in order to give them the chance to succeed," says Christopher.

"There are so many stereotypes about what homelessness looks like—a lot of people believe that it's their own darn fault that they're homeless and all they need to do is get a job," says Ken.

She's like a hero to those kids. By watching her achieve what she achieved, they have also learned that they can overcome whatever obstacles life is going to pose. That's one of the most important things we do, is demonstrate to the children the capacity of their parents to succeed, which teaches the kids, 'I can do it, too.'

Christopher Fay, Executive Director

Kim, too, sees a future where Kidstretch scales alongside Homestretch and serves children at a greater variety of ages. "My dream would be to offer Kidstretch from infancy to five-years-old. That's our long-term hope for Homestretch, to be able to offer that to parents," says Kim.

Our vision is to change the entire narrative in this country about what a homeless family can do. About who is homeless and what they're capable of, so we start changing the way we treat them. We treat them as fully capable human beings and invest the kind of time and energy that they need to really flourish. That's the most important thing we could do.

Christopher Fay, Executive Director

***

Learn more about Stand Together's efforts to make the economy work for all and explore ways you can partner with us.