When was the last time you traveled more than three hours round trip to go grocery shopping?

The South Dallas neighborhood of Bonton is a three-hour bus ride to the nearest grocery store. If you add to that time spent in the store and multiply it by an average of six shopping trips a month, residents spend 21-24 hours a month just getting groceries.

Sounds like a lot, doesn’t it? The people of Bonton cut down on travel time by also visiting local convenience stores and fast food restaurants — poor substitutes for the quality food that takes so long to get to.

The USDA estimates that 53 million Americans live in similar conditions. Bonton is a “food desert” — a populated area that lacks adequate access to healthy, affordable food. The United States has approximately 6,500 of these “food deserts.”

Bonton, a century-old South Dallas neighborhood, is a classic food desert. Spanning just 2.5 square miles, 63% of residents don’t have cars. It’s isolated by a river, a highway, and a railroad. The entire community is cut off from essential resources like food, jobs, medical care, and economic opportunity.

“Everything that we need, the goods and services — and even the jobs — are in other places,” Daron Babcock, founder of Bonton Farms, said in a 2019 TED Talk. Residents struggle just to get by, let alone improve their circumstances.

Babcock founded Bonton Farms in 2014 after realizing limited access to quality food was affecting his Bonton neighbors’ health. Today, the nonprofit has the country’s two largest urban farms, offering jobs and produce to community members. Despite this, nutritious food remains scarce, so Bonton Farms created Grocery Connect, an innovative solution that allows residents to shop online — a novel experience for most — and get weekly deliveries from Kroger, a national grocery store chain.

It sounds simple, but residents of Bonton harbor doubts rooted in decades of broken promises and companies leaving their community after brief stays.

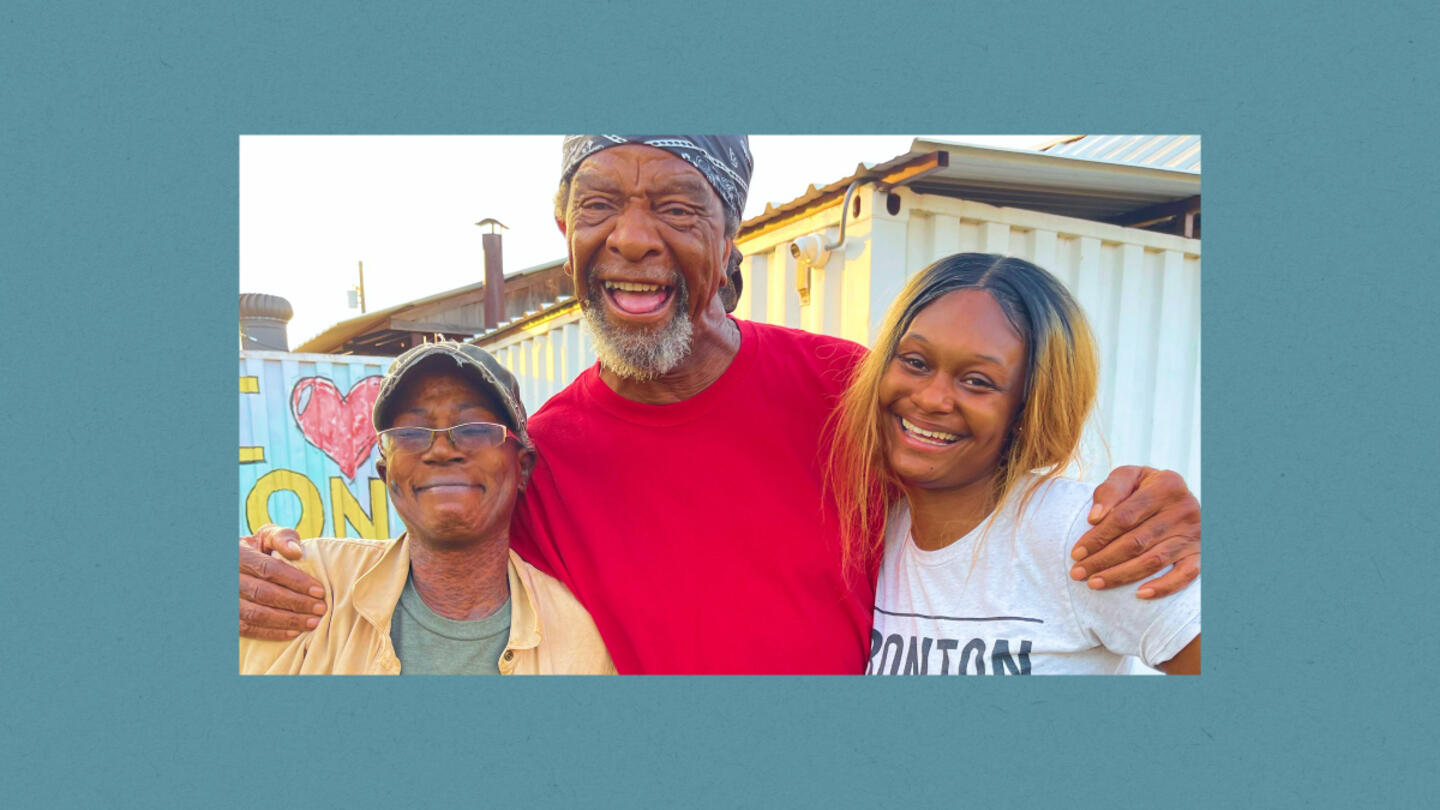

“One of our primary goals in fighting systems of inequity is relationship building with people in our community,” said Gabe Madison, president of Bonton Farms. “We understand this is a vital first step in working alongside our neighbors to get the resources needed for our community.”

Bonton Farms is coaching Kroger on how to operate in a market unlike any the grocery chain has ever entered. Trust is key. Long-term success hinges on Bonton residents believing Kroger is authentic, that it will consistently show up and demonstrate the same care and respect it gives all Dallas shoppers.

Could the Grocery Connect model be a way to end food deserts for good?

How do food deserts happen?

Babcock, a businessman 10 years into his recovery from cocaine addiction, sold his home and moved to Bonton in 2012. He had been volunteering in the neighborhood once a week in a Bible study group with men who were recently incarcerated.

“Those men changed my life,” he said in his TED Talk. “When people ask me why I moved there, I often just say, ‘Well, sometimes you see things that you can’t unsee.’”

He spent those initial years building trust, uncertain if the community would accept him, outsider that he was. He wanted to serve the community, but first he needed to get to know his neighbors.

Many people told Babcock that Bonton’s greatest need was jobs, so he began organizing community projects and hiring local residents to help him. But workers frequently called in sick.

After a while, Babcock realized people weren’t suffering from recurrent cold and flu symptoms. These were severe chronic diseases like diabetes and kidney failure — abnormally common in this small neighborhood.

Living in a food desert has lasting consequences. In Bonton, chronic disease rates are significantly higher than the rest of Dallas: 54% more cardiovascular disease, 45% more diabetes, and 58% more cancer. Health challenges impact residents’ ability to work and engage in community life, making it even more difficult to access resources or improve their circumstances. Though not impossible, it is hard to break free from this cycle.

Food deserts don’t happen spontaneously. They’re often the downstream impacts of outdated, historically biased policies that hinder community growth. Bonton Farms regularly unearths these policies. For instance, 60 years ago, federal housing projects doubled Bonton’s population without increasing local resources. Additionally, 85% of the area is zoned for residential housing, which makes it hard for commercial developments to move in.

Other issues are not so obvious, and Bonton Farms doesn’t find them until it trips on them — like when Babcock built the first farm. “We got a ticket,” said Madison. “You couldn’t have a farm in the city. This was a real thing; city ordinances denied people having their own farms.”

Providing healthy food is one of the ways Bonton Farms is disrupting the cycle. “We’re laying a foundation where health, wellness, and opportunity are the norm for everyone,” said Madison.

“We’re talking about a foundational layer of nourishment,” said Samuel Newman, Bonton Farms’ director for Grocery Connect. “The one thing that connects us all is the need for nourishment. We’ve learned that good food demand exists everywhere. Supply does not. So how do we attract the supply in a way that proves the demand?”

Sign up for the Strong & Safe Communities newsletter for stories, ideas, and advice from changemakers working with their neighbors to address the biggest problems we face.

How to build trust in a skeptical environment

Establishing trust in Bonton is not a simple task for outsiders.

Experience has taught residents to be wary of anything new. Outsiders don’t usually stay long. “Either it appears for a minute, and then it disappears or never comes,” said Madison. “So there’s a lot of skepticism.”

For most community members, continuing their old habits, however arduous, feels easier than believing this offering from an outside company will be different.

“There aren’t many people walking out of their front doors, wondering where groceries come from,” said Newman. “They’re figuring it out. They can’t not figure it out. We’re trying to change the expectation of what can come to this neighborhood.”

But there’s a dilemma. Kroger and similar companies base decisions on revenue, and proof of profitability is important to new ventures. However, in Bonton, revenue growth depends on cultivating trust, which requires consistency and time to develop.

As part of its discovery process, Bonton Farms asked 120 residents to describe their journeys to food access. The recurring theme in these “journey maps” was the relational aspect of accessing food — from shared rides to meaningful interactions at the grocery store and bus stop.

The nonprofit then asked prospective grocery store partners how they would build relationships with the people of Bonton and demonstrate their commitment to individuals and the community.

“Kroger’s commitment was that the delivery person would not just drop the groceries off,” said Madison. “They would stay the entire time and get to know the community members. Then they could advocate for them back at the fulfillment center.”

She shared a hypothetical example of “Ms. Jackson.” The delivery driver gets to know Ms. Jackson and learns that she doesn’t care for holes in her collard greens. Back at the fulfillment center, if the driver sees any subpar greens, he’ll refuse to load them, insisting on a better batch.

Ms. Jackson gets more than quality groceries. She feels heard. “It’s this feeling of ‘You understand who I am, and you understand what I like,’” said Madison.

“Ms. Jackson knows that when the blue [Kroger] truck comes, someone has thought of her,” said P.J. Johnson, Grocery Connect’s marketing manager. When Ms. Jackson approaches, the driver and other team members greet her by name. “Hi, Ms. Jackson, how are you? We got this, Ms. Jackson. Have a good day, Ms. Jackson. How are your grandkids doing, Ms. Jackson?”

It chips away at Ms. Jackson’s skepticism because the delivery driver, acting as a proxy for Kroger, demonstrates that Ms. Jackson deserves the same excellent treatment customers receive in other parts of Dallas.

“Families are not just getting what they need physically,” said Johnson.

‘I thought it was for the rich people up north, but it’s for me.’

Bonton Farms knew going in that this transition would take time for the community. A lot of what the organization is doing in the first phase is helping people get used to seeing Kroger in the neighborhood.

“Our hope is that they continue to see the truck pull into the parking lot every week and say, ‘Well, it’s still here. You know, this looks like it’s really happening,’” said Madison.

“Delivery day is a bit of an event,” said Newman. “We set up a nice tent outside. We pass out waters. The nice little box truck drives up with the Kroger brand. … It’s a welcoming place. We want it to be as public as possible so people can see that Kroger is in the community every week.”

Grocery Connect is still in the early adopter phase, with about 40 consistent customers so far. Every week, a few more people walk up and ask what is going on. The first site is accessible to 7,000 residents in Bonton and nearby neighborhoods. Two more pickup sites are in the works and will expand the reach to 15,000 residents.

Kroger is in it for the long haul. Bonton Farms set the expectation that this level of trust would take more than a few months. In the meantime, Kroger is gaining unique insight into a market it has overlooked for years.

Community members are learning to expect genuine care and meaningful connections. Madison has heard them say things like, “I thought Kroger wasn’t for me. I thought it was for the rich people up north, but it’s for me.”

“That’s what warms my heart,” said Madison. “It’s for people to believe it’s for them.”

***

Bonton Farms is supported by Stand Together Foundation, which partners with the nation’s most transformative nonprofits to break the cycle of poverty.

Learn more about Stand Together’s efforts to build strong and safe communities and explore ways you can partner with us.

At this ‘resort,’ children with intellectual disabilities are seen as gifts to be celebrated and loved.

Veterans experience loss when leaving service. Could this be key to understanding their mental health?

The Grammy-nominated artist is highlighting the stories we don’t get to hear every day.

With his latest project, Blacc isn’t just amplifying stories — he’s stepping into them