When Brandi Fields woke up in the ICU, she was told she’d never walk again.

Her stepfather shot her multiple times after an altercation at a family gathering. One of the bullets struck her spine, paralyzing her from the shoulders down.

She refused to accept the prognosis. “I immediately told them, ‘No. Not for long. I’m gonna walk,’” she said. Just six days later, she began moving her right big toe. Determined and surrounded by support, Fields took her first steps five weeks after her injury. “They were assisted steps, but they were my first steps.”

Her injury was life-altering. Fields became one of over 40 million adults in the United States living with a physical disability — people whose lives are defined more by what they can’t do than what they can do.

Fields didn’t like those limits. Ever since that first day in the ICU, she’s been pushing against them.

“We talk about things that we can and cannot do,” she said. “I don’t believe there’s anything that you can’t do. You just have to find an adaptable way to do it. And that’s what I’ve been doing this entire time, up until, you know, coming to ATF — and then doing a whole lot more.”

Adaptive Training Foundation in Dallas is more than a gym — it’s a place where individuals like Fields, who have experienced life-altering injuries, are recognized as athletes. Each ATF athlete arrives with their own story, but they share a common goal: to challenge their limits and refuse to let their disabilities define them.

For Jimmy Donaldson, better known as the world’s No. 1 YouTuber MrBeast, ATF represents everything he loves about the world. As online media’s leading philanthropist and a powerful influencer, MrBeast is using his platform to inspire kindness and positive change worldwide. He creatively showcases organizations like ATF through his Beast Philanthropy channel, amplifying their inspiring work.

Beast Philanthropy and Stand Together share the belief that every person has the potential to achieve amazing things no matter what challenges they’ve faced. This shared vision led the two organizations to collaborate in support of ATF.

A deep sense of community drives the athletes’ progress at ATF. They push each other to new heights in the gym, fostering high expectations and celebrating every victory together. This shared belief in people’s intrinsic strength and their ability to overcome challenges is transformative. That belief — first in others, then in themselves — becomes the most powerful force helping ATF athletes change their lives.

“Once we start to get a bunch of people together with an attitude to just try and see what can happen, that’s where the magic lies,” said former NFL player and ATF founder David Vobora.

Doctors may say a person will never walk again, but they haven’t seen what’s happening at ATF.

Hard to believe? MrBeast thought so, too, which is why he sent a team from Beast Philanthropy to Texas — to spotlight this incredible nonprofit and, in true MrBeast style, surprise Vobora with a special gift.

The results are something you have to see to believe.

Life-altering injuries affect much more than just the body

Every ATF athlete has a story most of us couldn’t imagine.

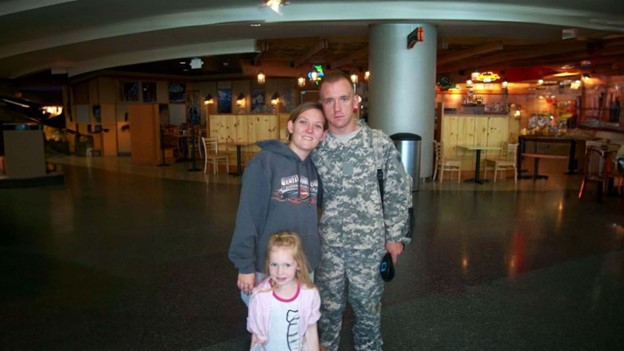

U.S. Army Specialist Bo Jones stepped on an improvised explosive device (IED) in Afghanistan.

“I stepped on the IED, and I lost both my legs.”

Shelby Estocado was paralyzed when she lost control on a snowboarding jump and broke her spine and sternum.

“I had a snowboarding accident, and I suffered a T6 spinal cord injury.”

At 19, Ryan Chen was snowboarding on a 35-foot jump when he over-rotated on a flip and shattered his spine.

“I couldn’t see the landing. I landed on my back and shattered my spine.”

U.S. Marine Corporal Neftali Mendoza suffered a ruptured aortic aneurysm due to non-combat trauma related to his military service.

“I suffered a triple A (AAA) aortic aneurysm.”

Brandi Fields’ stepfather shot her multiple times. One of the bullets struck her spine, paralyzing her from the shoulders down.

“He shot me three times without hesitation. I was instantly paralyzed.”

The prevailing narrative in medical communities regarding injuries like these is that patients should be grateful simply to be alive. However, the psychological toll is far more complex.

“I can only imagine the devastating feeling as they realize the significant impact this will have on the rest of their lives,” said MrBeast.

Sign up for the Strong & Safe Communities newsletter for stories, ideas, and advice from changemakers working with their neighbors to address the biggest problems we face.

Jones struggled. He went from being a healthy, fit 21-year-old serviceman to waking up in a hospital, unable to even feed himself.

Mendoza described his mindset as being very negative. “I hated the way I looked,” he said. “I hated the way I felt.” He had been attempting jiujitsu as an amputee and trying to move forward with his life, but sometimes it became overwhelming, making him want to give up on more than just the sport.

The psychological pain is often compounded by persistent physical pain. “I was crying, and I was in pain from the nerve pain that I had since my accident,” said Chen. “I think rock bottom was really me, debating whether I wanted to live this life — whether this was, you know, a life worth living.”

Medical treatments often emphasize “functional rehabilitation,” or maintaining basic function. While achieving this is important, the idea that care ends there fails patients. It places limits on their potential and neglects the emotional impact of their disabilities.

“All of these people have been sidelined,” explained Vobora on the ATF website. “They went through the rehabilitation process, but eventually insurance ran out, cash ran out, and where do they go? Where do they go to be a part of a collective group that has this community and this ability to push each other?”

Despite what many saw as hopeless circumstances, these athletes had to come to terms with their new life paths.“Something amazing happened,” said MrBeast. “At a point that was undoubtedly one of the lowest of their lives, they decided to not give up, but rather, to fight harder and excel at life despite the change in circumstances.”

“I started surrounding myself with people that told me what I didn’t see in myself,” said Jones.

“I never want to feel that low and that helpless and that weak again,” said Mendoza. “I had to stop feeling sorry for myself.”

For Vobora, it all starts with believing in people until they can believe in themselves.

A quadruple amputee bench pressing? No joke

“I walked directly up to him without hesitation, full eye contact, and I said, ‘How much do you bench with that one arm?’” said Vobora. “And he said, ‘What did you just say to me?’”

That was his first conversation with Travis Mills, 1 of only 5 veteran quadruple amputees in America. The two met through at a birthday party for a mutual friend. It changed them both forever.

Mills was stunned at first, thinking Vobora might be joking. But Vobora was serious. He teamed up with Mills, and together they explored new ways for Mills to push his body physically. It was uncharted territory for both of them.

“I started with him, and then I had another veteran, and then 10, and then 20,” said Vobora. “And I think that was the catalyst for me to go, ‘We can’t stop doing this.’”

At the time, Vobora was in his own physical and psychological recovery. Once a linebacker with the Seattle Seahawks, Vobora sustained a devastating shoulder injury and became addicted to painkillers — one of the 16 million people affected by the opioid crisis. He spent his recovery trying to understand who he was without football.

Though the injury ended his football career, he enjoys a new kind of physical challenge now.

On the wall at ATF hangs a bell. When athletes reach a new personal record (PR) or do something they didn’t believe was possible, they ring the bell. Everyone in the gym stops and celebrates with the athlete.

“The difference in [football] and the way that I get to do what I do now,” he said, “is when that bell rings, and I get to be right there, and that person has that moment, there’s this really cool kind of balance that gives me this hit of ‘nothing can be more important than exactly where I am, right here, right now.’ But the difference is, it doesn’t wash off.”

‘Stuff I never thought that I would be able to do’

A certain synergy happens when people who’ve lived through similar experiences do hard things together. They start to heal inside and out.

When Darren Margolis, executive director of Beast Philanthropy, and Dan Mace, chief creative officer, visited ATF, they were impressed by a system the athletes call “sweat equity.”

“We all sweat together, and we all bond together through working out,” said Mendoza. The bonding happens as athletes discover new ways to exercise despite their disabilities, while also practicing mindfulness to heal the trauma of their injuries and reconnect their mind and body.

“People with shared experience are best equipped to help their peers because they understand the challenges so much better,” said Margolis. “[At ATF] this shared experience and understanding has built an incredible community of athletes that are fully invested in helping every single person achieve their highest potential.”

Jones called the ATF experience “life-changing.”

While Margolis and Mace were visiting, Fields attempted a new personal weightlifting record.

“I was in my head a little bit, but I had to dig deep,” she said. “So many people around me, cheering for me, knowing I had that support. I was like, let me do anything I can to get this weight off the ground.”

“I did it, and it felt amazing!”

After lifting 220 lbs., Fields placed her hand on a teammate’s shoulder for support and confidently walked over to the bell, ringing it loud and clear.

“This is some stuff I never thought that I would be able to do,” she said. “So lifting 220 pounds? You can’t tell me nothing.”

“This is such an important lesson to every one of us,” said Margolis. “Our own struggles and achievements may be a breakthrough that someone else desperately needs. Sometimes you will even find that helping others is the breakthrough you need.”

Chen said his younger self would never have believed life could be so good. “If I could go back in time and tell my 19-year-old self that I was gonna be okay, I wouldn’t believe it,” he said. “Let alone the fact that I would be able to fly a plane one day, that I will start a company with my best friend and be able to make my parents so proud.”

Margolis was inspired by how much work he saw happening at the gym. These people were fighting as hard as they could. He was even more struck by how happy the ATF athletes were and that many said they wouldn’t undo their injuries. It gave him goosebumps.

“Everything in the universe happens for a reason,” said Jones. “If I had never stepped on that bomb, I never would have been able to see, one, what I was truly made of, but also how I could help the world in a more positive way.”

“After going through my injury and being where I am now, and having the perspective I have on the world, I feel like I’m a stronger person than I ever could have been,” said Chen.

Margolis and Mace wrapped up their visit by tossing a football with Vobora. For each catch made by Margolis or Mace, Beast Philanthropy and Stand Together donated $50,000 to ATF. The final prize: $250,000 to support Vobora’s mission of helping people transform their lives.

Personal transformation — physical and mental — has always been the goal. Each ATF athlete is on a quest to achieve the best version of themselves while helping others do the same.

“We’re not gonna make this gym about changing the world for them,” said Vobora. “We want it to change them for the world.”

“This is a lesson for every one of us with whatever challenges we face that feel so overwhelming to us,” said Margolis. “Don’t give up, and you will surprise yourself with your own inner strength.”

Beast Philanthropy is currently leveraging its network and community to help ATF raise funds to build a four-acre, 30,000-square-foot training facility near Dallas. Vobora aims to expand ATF's reach by training not only more athletes but also adaptive athlete coaches who can bring this transformative program to their own communities.

***

Adaptive Training Foundation is supported by Stand Together Foundation, which partners with the nation’s most transformative nonprofits to break the cycle of poverty.

Learn more about Stand Together’s efforts to build strong and safe communities and explore ways you can partner with us.

At this ‘resort,’ children with intellectual disabilities are seen as gifts to be celebrated and loved.

Veterans experience loss when leaving service. Could this be key to understanding their mental health?

The Grammy-nominated artist is highlighting the stories we don’t get to hear every day.

With his latest project, Blacc isn’t just amplifying stories — he’s stepping into them