Are you the hero in your life story?

For currently and formerly incarcerated individuals and their families, society often casts them as the villains. What if they could author their own story instead?

Founded by Dani Hedlund, The Brink Literacy Project works with people in under-resourced communities, prisons, and reentry programs, helping them reflect on their lives thus far and create graphic memoirs that reimagine their life stories. Incarcerated individuals can recast themselves and their trajectories — but the first step is to share their own stories, as vulnerable as that may be. Once they see that others present have struggled through the same challenges, new possibilities emerge.

Though it may seem simple, this can be a transformational moment for many participants as they learn to see themselves differently — and begin to believe a better future is possible.

“Our class is a bit of sneaky therapy,” Hedlund said. “When the only ideas that you have about yourself are things that other people tell you, you can only be as big as what other people imagine you to be. But when you engage with other stories, it opens up the entire world.”

Comic books, or graphic novels, are especially important to this kind of narrative. Comic books contain themes that prompt students to reflect on important, big-picture questions, such as, “What are the things that people think about you that probably aren’t true?”

“When we start to empathize with the characters on the page, we start to think of ourselves as the heroes of our own stories,” Hedlund said. That can have life-changing implications.

When storytelling leaps off the page and into our lives

Hedlund knows firsthand how dramatically storytelling can change lives. She is Student Zero of the Brink Literacy Project.

“I grew up in this tiny little farm town,” she said. “It was definitely one of the places where you’ve been told your whole life that you will never get out. I thought of myself as someone who wasn’t smart.”

Like many young people, Hedlund had trouble reading and internalized that trouble as an indicator of her overall intelligence. As a result, she kept her struggles a shameful secret.

“Literacy is the primary way in which we can advocate for ourselves, but 54% of Americans can’t actually read above a sixth-grade level,” said Hedland. And she should know — she was one of them. When she was 13, she finally told her dad. His response was the opposite of what she expected.

“He was like, ‘Don’t feel like you’re stupid,’” she said. “‘I know how smart you are.’”

He had a surprising suggestion for her: comic books. The visual elements combined with fewer words allowed a young Hedlund to more easily grasp written stories. Reading comic books unlocked a domino effect of increased academic aptitude and, more importantly, confidence that altered the trajectory of her life.

“Not only did it help me get the skills I needed to get a scholarship so I could get out of that town, but more than anything, those stories changed the story that I told about myself,” she said. “That I was smart enough, good enough to write my own story. When I thought about my own narrative, I thought, ‘Maybe the struggles that I’ve had are something that could help other people.’”

Now, Hedlund is helping others access the same transformation she experienced, building on that simple tool her father gave her so many years ago. How does she do it? A book club.

Sitting around a table of adult participants poring over loose pages of a graphic novel, Hedlund advised them, “Think about the main characters that are going to be in your story. There’s usually an ally. There’s usually a villain. Sometimes, we are the villains.”

Under the outward-facing focus on literacy, the Brink Literacy Project uses methods. Students use open conversation and reflection to grapple with difficult questions and turn the lens back on their own life patterns. At the end of the course, students have written and produced their own graphic memoirs based on their lives, which are then published in Brink’s bespoke literary anthology, “F(r)iction.”

“We go into populations where people have been told their entire lives that they’re worthless, that they’ll never amount to anything,” Hedlund said. “They often have a huge feeling of villainy.”

That’s a feeling that Jay, a participant in the program, knew well. After spending most of his youth in and out of jail, he could empathize more with the bad guys than the good.

“Growing up, I wanted to be a mob boss,” he said. “Kind of like my dad in that ‘hood life.’ But my uncle took me under his wing. He played a huge part in my life.”

Jay’s uncle seemed like a hero — he was even on the way to playing in the NBA. But when he found out he had a baby on the way, he began to worry about being able to provide for his family. He fell back into drug dealing alongside Jay’s dad.

While on that path, Jay’s uncle was murdered. Suddenly, Jay understood what happens to villains at the end of the story.

“That changed my whole life,” he said. “I was really confused because I saw my uncle as the way out of that hood life. Struggling with that nightmare of I might fall into the same situation.”

For a time, he followed that path, eventually dealing drugs himself. But when Jay’s daughter, Lilliy, was born, he resolved to rewrite his story, determined not to set an example that might lead her down the same road he and his uncle had taken.

“She saw her dad making more money without going to work,” he said. “So that started to trickle down [to] her. That didn’t resonate well with me. I wanted to teach Lilliy something different.”

Jay was offered a new job on two conditions: stop selling drugs and attend a Brink Literacy Project class.

Sign up for the Strong & Safe Communities newsletter for stories, ideas, and advice from changemakers working with their neighbors to address the biggest problems we face.

In class, students learn basic literary structures and then reflect and apply them to their own lives. This follows a classic storyline of establishment, climax, turning point, and finally, a resolution.

“When we start talking about these incredible story arcs where people have essentially made bad choices for good reasons, there’s always this great ‘aha’ moment in our classes when someone says, ‘Oh, I know what those struggles are like,’” Hedlund said. “The idea is for them to hone in on a moment in their lives in terms of turning points when you made one decision, and if you’d chose differently, your life would be radically altered.”

This can involve a difficult process of accountability and taking ownership of how bad decisions have resulted in negative outcomes. But there’s an empowering angle: the realization that we can each rewrite our narratives and lift ourselves.

At first, Jay was doubtful.

“Why do you guys want to hear this?” he remembered thinking. “What’s the goal of hearing me tell you what I did wrong?”

But gradually, his community of fellow students started sharing their own stories. Whether describing their struggles with cycles of incarceration, crime, poverty, or other challenges, many of them had similar fears and hopes.

“I just watched everyone’s barriers start to drop,” Jay said. “They listened to our stories and gave feedback and didn’t judge us.” That encouraged him to share his own journey more openly and begin to reflect on what could have been different — as well as how he could change his future.

“When we think about those turning points, we realize, ‘Actually, my decisions had enormous power in shaping who I was,’” Hedlund said. “They can decide whether or not ‘I’m going to be a villain’ or ‘I’m going to be a hero.’”

Writing your story is just the first step. Transformation comes from sharing it.

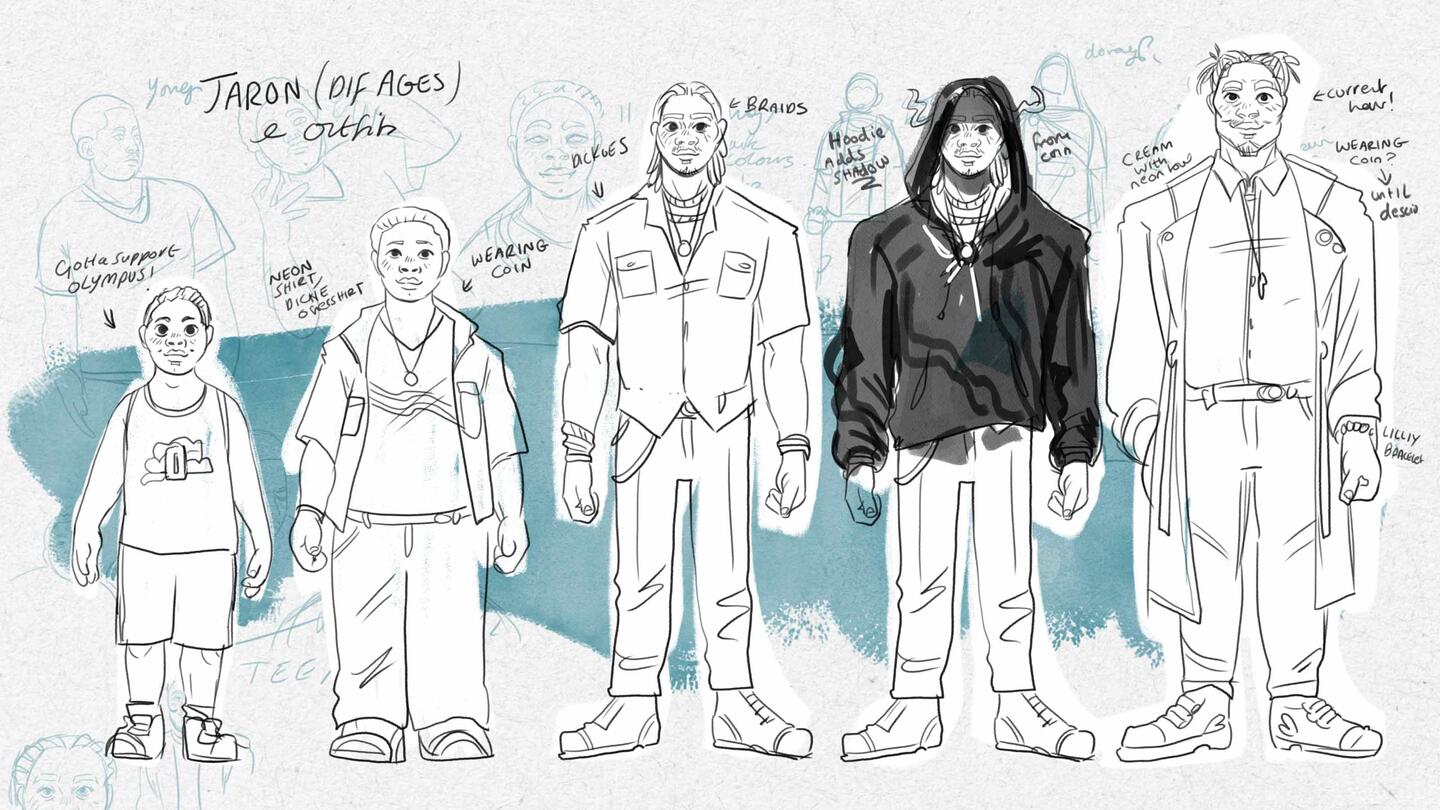

Jay worked with the Brink Literacy Project for over a year, reflecting on his past choices and traumas. He was able to gain such a level of introspection that he turned his life’s journey into a graphic memoir, written by him, complete with illustrations from a professional comic book artist that helped his story pop off the page.

“To be able to step back and look in on my life as a story, it gave me confirmation that this isn’t a down point, this is a turning point,” he said. “Your trouble or your felony or your experience is not you. It’s just something you did. I realized I didn’t want to be a mob boss. I wanted to be a leader.”

Jay had successfully rewritten his own life story and cast himself as the hero. What’s more, he would be able to share his story with others going through similar struggles and inspire them to believe they have the power to do the same: Brink’s “F(r)iction” anthology is shared globally in huge stores like Barnes & Noble. The magazine is also circulated in hundreds of prisons across the United States.

“Stories could change anyone’s life,” Hedlund said. “Not only as a teaching tool for students just like Jay, but also as a tool to help people change the way they think about this population.”

“It was amazing to see … a negative, hurtful failure in my life … pictured as a flourishing moment,” Jay said.

To frame it in a Brink-approved way?

“My origin story,” Jay said, grinning.

Perhaps one of the most meaningful moments was Jay’s ability to share his graphic memoir with Lilliy — after all, she played a pivotal role in his turning point. In doing so, he was exemplifying the most important part of the Brink Literacy Project: sharing our stories with others.

Nearly all participants (97%) in Brink’s courses cite increased confidence, hope, and faith that they could thrive in life, while 83% continue to further education or career training. And 100% say they would recommend the program to a loved one. By sharing their experiences and finished works, participants help others struggling with their self-image and life choices achieve the same.

“We want students who have gone through our programming and had incredible transformation,” Hedlund said. “But we always want that next step, which is, ‘I’ve been changed. I want to help other people change.’ And Jay has that in spades.”

In only a year, Jay didn’t just go from skeptical and pessimistic to self-confident and determined; he also transformed from Brink student to instructor-in-training.

Speaking to a new cohort of Brink participants around the table, Jay said, “Within this class, if you’re ever like, ‘I don’t want to tell everybody all of that,’ that might be what you want to dive into. Because that’s where that reader is really going to connect with you.”

“What we hope from engaging with these stories is [that] the story they tell themselves isn’t, ‘I deserved that, I’m wrong, I’m the villain,’” Hedlund said. “But instead, ‘I deserve to have a better life than what’s been laid out in front of me, and so the next time I’m at this huge crux point, I’m going to make the good decision.’”

Jay’s story is featured in the Spring 2025 issue of “F(r)iction.” You can preorder it here.

Brink Literacy Project is supported by Stand Together Foundation, which empowers individuals to reach their full potential through community-driven change.

Learn more about Stand Together’s efforts to build strong and safe communities and explore ways you can partner with us.

People with disabilities want meaningful work — and Hugs Cafe is making it happen.

At this ‘resort,’ children with intellectual disabilities are seen as gifts to be celebrated and loved.

Veterans experience loss when leaving service. Could this be key to understanding their mental health?

The Grammy-nominated artist is highlighting the stories we don’t get to hear every day.