In 2011, Pastor Corey Brooks presided over 21 gang funerals at a time when other ministers felt it was too dangerous. The funerals were all for boys and young men between the ages of 13 and 25 who were killed by gun violence in the Woodlawn community of South Chicago.

Moments before the 21st funeral, mourners came under gunfire as they walked to the church. People dove under cars and ran into the church building. “It was scary,” Brooks recounted in an oral history about violence in Chicago. “I’ve never experienced anything like that in my life.”

Somehow, nobody was hurt. Brooks decided to continue the service. “When people are hurting, that’s when we’re supposed to be there the most,” he said in an interview with Chicago Magazine about the incident. The funeral proceeded with police present to keep the peace.

When the service was almost over, Brooks spoke with the police sergeant in the room. They invited anyone carrying an illegal weapon to turn it in on the spot, no questions asked. Complete silence followed. Finally, a young man in the back of the room stood up and pulled a 9mm Glock out of the waistband of his pants. Across the room, another young man stood up and pulled out his gun. And then another stood up, and another.

“I decided right then, I’ve got to do something,” Brooks said in the interview. His solution: Recruit gang members to work on the problem. “We started to work with [gang recruits] to teach them the ways that violence has impacted our community, but also the ways that they need to now turn their lives toward trying to help fix the issue,” he told Federal Newswire in an interview last year.

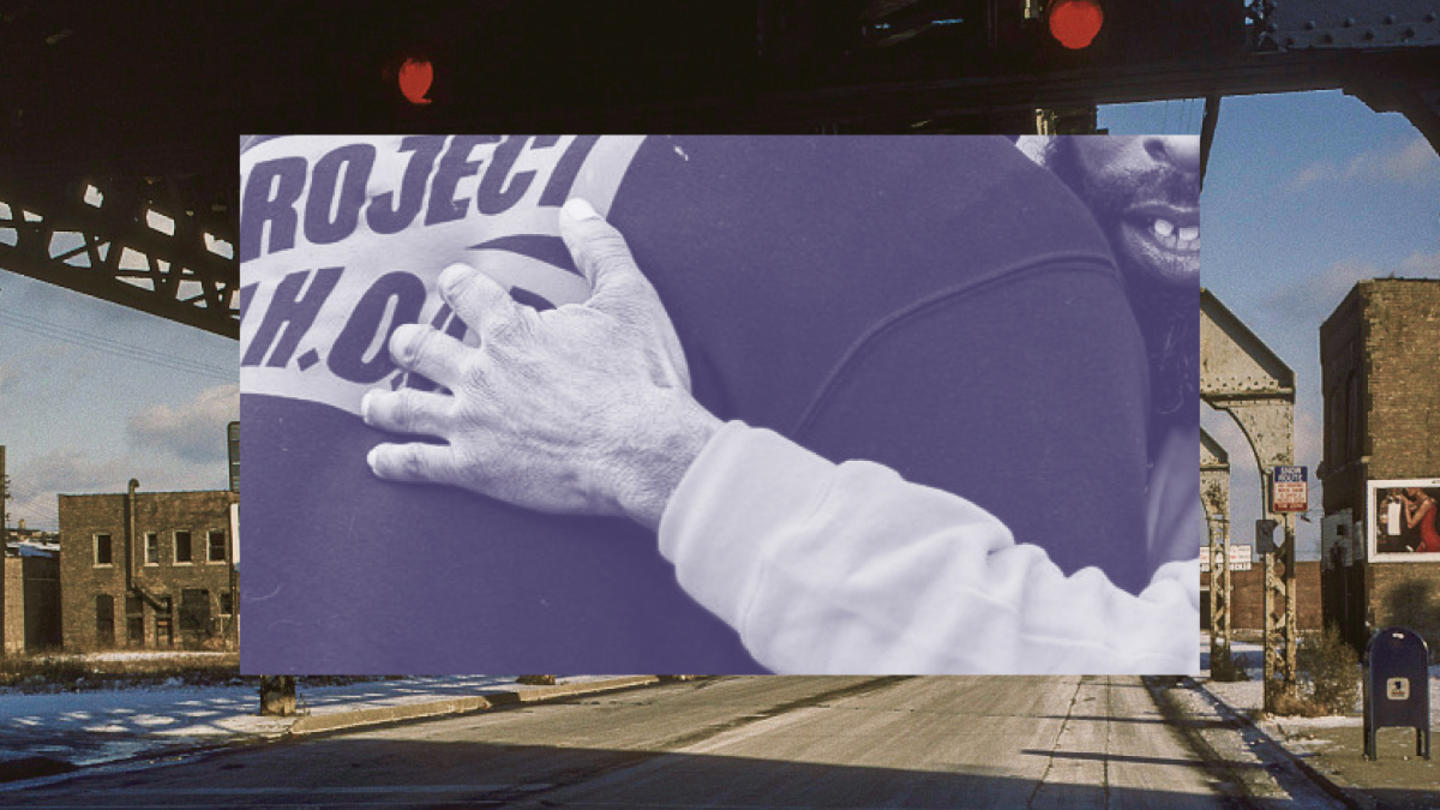

Soon after, Brooks founded Project H.O.O.D., which stands for “Helping Others Obtain Destiny.” Since 2012, Project H.O.O.D. has worked in Chicago’s Woodlawn community to lower homicide rates by 52%. The organization is leading local efforts to replace negative street activity with constructive community programs. All of Project H.O.O.D.’s employees and volunteers are deeply embedded in the community. They are working together to reclaim their neighborhood as a place where residents can feel safe — a place where individuals and families feel empowered to grow and improve their circumstances.

Brooks’ work isn’t about tightening control or forcing people to live a certain way. It’s about expanding opportunities and showing people what’s possible when they make better choices. “When people are empowered — every individual — they start to see for themselves that they can change the direction of their lives,” Brooks said in his interview with Federal Newswire. “They don’t have to wait on anybody to do it for them.”

In some parts of Chicago, violence is all-too-common

Chicago’s reputation for violence is not undeserved. A 2022 review of historical data revealed that young men living in some Chicago zip codes are more at risk of injury or death by firearm than soldiers in either the Iraq War or the Afghanistan conflict.

For the last two years, the average number of homicides in Chicago has been 770. In 2021, Chicago was sixth in the nation for high homicide rates. But the violence isn’t evenly distributed. It’s concentrated in Chicago’s south and west sides. Woodlawn experienced 10 homicides per 100,000 people in the last 12 months. Hyde Park, the neighborhood that shares Woodlawn’s northern border, saw only one homicide per 100,000.

Violence is as much a symptom as it is a problem. Poor neighborhoods lacking educational options, upward mobility, or job opportunities tend to have higher crime rates. “A lot of kids in this neighborhood feel like they don’t have anything to live for,” Brooks said back in 2012 before founding Project H.O.O.D. “They don’t have any education, they don’t have any jobs, they don’t have any family, so what’s the point?”

Brooks used to expect the government to help people in poverty. Not anymore. Now he recognizes that government officials are too far removed from the challenges his community confronts every day. Referring to policymakers promoting movements like Black Lives Matter and Defund the Police, Brooks wrote in Newsweek, “These movements have all been pushed by elites in the name of helping Blacks, but not one of these people has ever visited my neighborhood to ask what we think.”

Violence is like a disease

Years ago, local gangs nicknamed Woodlawn “O Block” after a murdered gang member. The name has become infamous. O Block sits at the crossroads of several gang territories and is prominently featured for its violence in rap culture. In 2014, the Chicago Sun-Times ran a story about O Block’s high homicide rate with the headline, “‘O Block’: the most dangerous block in Chicago.”

“Project H.O.O.D. took offense to that,” said Desmond Marshall, president of the nonprofit. “We said, ‘Hey, we can do something about this.’”

Brooks described the decision this way: “We decided to hire individuals from most of the gangs that are functioning in our neighborhood, two or three full-time individuals from those areas, train them on trauma counseling, conflict resolution, help them to redevelop their mindset and soften their hearts.”

James Highsmith directs Project H.O.O.D.’s violence impact team. He spent 20 years in prison for gang activity in South Chicago. He now uses his “street credentials” to dissipate violence in O Block. His team is composed of local community members, many of whom have lost loved ones to gun violence. Others are former gang members.

“We have these individuals working from different gangs who used to be enemies of one another — they would call themselves ops or opposition — who are now working together,” Brooks said in an interview.

Highsmith’s team focuses largely on preventing retaliation shootings. “Violence is like a disease,” he told Brooks in a 2022 interview for Fox News. “What we try to do is interrupt the transmission between violence being spread from one individual or from one group to another.”

Whenever there is a shooting, a member of the violence impact team shows up at the hospital with the family — both to offer support and get a feel for family members who may be planning to retaliate. The team identifies the people responsible for the shooting and the circumstances involved. They work with both sides to try to curb tensions and prevent further violence, which may include mediating a conversation to resolve their conflict with words, not guns.

Project H.O.O.D.’s 40 part-time employees are largely former or current gang members. Highsmith said they keep his team abreast of gang activity and make it possible for them to avert tragedy before it happens. At a Woodlawn violence advocacy event, he described the network as the “most effective and the most powerful program that we have. It gives us a direct connection to the brothers and sisters that are most likely to get shot or do the shooting. Also, it gives us a direct connection to the neighborhood block-by-block. Because of those direct connections, we’re able to change the whole trajectory of shootings and killings in our neighborhood.”

Dubbed the “FLIP” team (Flatlining Violence Inspires Peace), Brooks said members of this network can get closer to gang members than anyone else on his staff — or in the city. They build and maintain relationships with gang members, all the while trying to draw them towards a better life.

“Their job is to go back to those corners, tell them about the resources, promote and recruit [just like the gangs do],” Brooks told Federal Newswire. “We recruit just like them. But the thing is, we have benefits. We have things that can assist them with their families, education, empower them — not disempower them — and that makes the difference.”

Ten years ago, Woodlawn — aka O Block — was the most dangerous block in Chicago. “We’re not even in the top 30 for homicides anymore,” said Marshall. Homicides have dropped 52% in 10 years. In 2022, Woodlawn homicides were down about 35% while its neighbor, South Shore, saw an increase of 11%.

Residents say Project H.O.O.D. is responsible for the change. Marshall said they won’t take all the credit, “But we’ll take our fair share of it.”

Sign up for the Strong & Safe Communities newsletter for stories, ideas, and advice from changemakers working with their neighbors to address the biggest problems we face.

Every individual is capable of transformation

Brooks and his staff believe in second chances. People who were once part of the problem can — and should — be part of the solution because they know better than anyone how to repair what they have broken.

Project H.O.O.D. is founded on the belief that “every individual is capable of transforming their lives,” said Brian Alexander, the nonprofit’s chief of staff.

Jeff “Rafi” Boyd gained his street credentials much like Highsmith. Having been involved in Woodland gangs in the 1970s and 80s, he spent nearly three decades in a federal prison before returning home and finding Project H.O.O.D.

While he was incarcerated, Boyd changed his mindset. “I came to the realization that I had to do something better with my life,” he said. “I had made some bad career choices, and so I made a conscious decision. I disavowed my membership with the [street] organization, stopped all other affiliations with it, and started educating myself and helping educate others.”

Boyd now leads the reentry program, helping recently incarcerated individuals integrate back into society. The fact that he, Highsmith, and other formerly incarcerated individuals are on the organization’s staff is a huge drawing card, he said.

“Project H.O.O.D. hires community people. That is the best example for a formerly incarcerated individual returning home,” he said. These individuals trust the staff because they’ve had similar experiences and know what it’s like to return to society. “I can honestly say that I walked that walk,” said Boyd. “I’m a street guy. I came from here. I went to federal prison. I changed my life.”

Speaking of his work in violence prevention, Highsmith explained to Brooks, “It’s not really that complicated when you got individuals who grew up in the area, know the individuals who are doing this, and get into the cracks and crevices of the community, where they get wind of situations and circumstances prior to them happening.”

Alexander said all of Project H.O.O.D.’s employees are from Woodlawn. “They’re connected deeply to the community. Many of them were enemies back in the day, and now they’re working to remedy the situation they helped create.”

Gang members need positive, local alternatives

A major goal since Brooks founded Project H.O.O.D. has been to build a community “leadership economic center” in the neighborhood. Brooks and his staff recognize that violence is a symptom of a larger problem. It’s not enough to tell young men and women not to join gangs. They need positive, local alternatives.

Marshall said every program and every pillar in the organization has been developed “based on the needs of the community.” Adults in the community lacked access to job skills training, so Project H.O.O.D. started a construction apprenticeship program. Some children in the neighborhood had never been to a museum or seen a swimming pool, so Project H.O.O.D. created a free camp for 250 kids every summer. And far too many members of the community have suffered violence-related trauma and loss, so Project H.O.O.D. began offering trauma counseling.

The new Leadership and Economic Opportunity Center is currently under construction. It will bring in resources and opportunities that haven’t been within reach before. For example, at present, there is no bank in all of Woodlawn. The new center will house the neighborhood’s first bank. It will also include an urgent care facility, a carpentry school, an automotive school, and an Olympic-size swimming pool — resources that will help residents of Woodlawn help themselves and their families.

“We call it the Miracle on King Drive,” Marshall said. “It’s about showing people what’s possible.”

From O Block to Opportunity Block

Brooks, Marshall, and the rest of Project H.O.O.D.’s staff have renamed O Block. “We call it Opportunity Block,” said Alexander.

The transformation is spreading. “People come from all around the city to our programming, even the suburbs,” said Marshall. “We can’t box ourselves in anymore. It’s like we’re a whole South Side nonprofit.”

“Governments can change laws, but they can’t change hearts,” Brooks said in his oral history. “It’s always easier to change a law, but as we see, even when they change the laws, nothing really changes around here. So changing hearts takes longer; it’s harder work; it’s a tougher task; it’s more daunting. But when you change a heart, it lasts for eternity. So my thing now is to help change people’s hearts.”

It’s been more than 12 years since Pastor Brooks first asked gang members to lay down their weapons, and he’s still at it. “Every person, regardless of their mess ups and mishaps, is deserving of a new, fresh start,” he said. In an interview with the Washington Times, he said, “We want to ensure everyone is empowered to change, and we’re going to give them the tools necessary to transform their lives.”

He continued, “Our goal is to get people out of gangs and to have them stop picking up guns and have them picking up hammers.”

***

Project H.O.O.D. is supported by Stand Together Foundation, which partners with the nation’s most transformative nonprofits to break the cycle of poverty.

Learn more about Stand Together’s efforts to build strong and safe communities and explore ways you can partner with us.

People with disabilities want meaningful work — and Hugs Cafe is making it happen.

At this ‘resort,’ children with intellectual disabilities are seen as gifts to be celebrated and loved.

Veterans experience loss when leaving service. Could this be key to understanding their mental health?

The Grammy-nominated artist is highlighting the stories we don’t get to hear every day.